Electric Trio Vol. 6: Halloween Quintet

'Satan's Rhapsody' (1917), 'The White Reindeer' (1952), 'Through the Looking Glass' (1976), 'Ogroff' (1983), and 'Loft' (2005)

It has been a long time since my last Electric Trio post (or any Electric Dreams post, for that matter) so I decided to use the Halloween season for a grand return by turning the usual mixed-bag trio into a quintet of horror films which are, you guessed it, underseen, underappreciated, and/or largely forgotten.

A quick note: I will be abandoning my Friday-only release tradition as reconciling the pleasure of writing with the necessity of making a living will require a little more flexibility on my part. So to the three readers who noticed and to the one reader who cared: I’m so sorry. Still, I hope you enjoy and, as always, thank you for reading.

Satan's Rhapsody (1917)

Nino Oxilia’s 1917 silent film Satan’s Rhapsody (often referred to by its original Italian title, Rapsodia Satanica) is, perhaps, more accurately categorized as a Faustian romantic tragedy rather than as a “proper” horror film, a genre descriptor that didn’t yet exist in the 1910s. The plot — Countess Alba (Lyda Borelli), an old, hunched-over woman, sells her soul to Mephistopheles (Ugo Bazzini) in order to regain her lost youth and subsequently meets two brothers (Andrea Habay as Tristano and Giovanni Cini as Sergio) who both fall in love with her — is rather thin but ultimately plays second fiddle to the extraordinary melding of performance, score, and visual lavishness on display.

In fact, trying to get at what makes the film so powerful without elaborating on the interplay between the acting and the music in particular is next to impossible. The actors’ movements sometimes call to mind the elegant, controlled movements of ballet dancers — the prologue features a remarkably serpentine performance from Bazzini as his Mephistopheles first emerges from a painting and then slithers and shifts around Alba’s legs — all enhanced by the soaring musical arrangements which push many of the film’s most striking moments further into lyricism. (A 2009 screening in Brussels even billed it as a “Cinematic-Musical Poem.”)

At only 44 minutes, Satan’s Rhapsody is remarkably dense, packing its brief runtime with more ideas than most features manage in double or even triple the time. Perhaps most astonishing, though, is the film’s second part which consists mostly of Alba aimlessly drifting through the vast of her estate as if in trance. Not only does it tip Rhapsody into a more hallucinatory tenor but it also anticipates some of cinema’s most celebrated works. The languid pace with which the final 15 minutes unfold would be found, decades later, in the likes of Last Year at Marienbad (1961), India Song (1975), and Nostalghia (1983) — as well as more than a few Antonioni films — while Orson Welles and Robert Clouse worked Oxilia’s haunting use of mirrors into a shot in Citizen Kane (1941) and the “room of mirrors” sequence in Enter the Dragon (1973), respectively. In the words of David Bordwell, “the film lets us…appreciate that the 1910s are not as far away as they might seem.”

The White Reindeer (1952)

Back in April, I featured a film called The Demon on the fourth edition of Electric Trio and mentioned its value as, amongst other things, an ethnographic study. Erik Blomberg’s 1952 fantasy folk horror film The White Reindeer falls into a similar category: setting aside for a moment its merits as a piece of filmmaking, the fact that it exists as a cinematic document of a place and its people, already makes it deserving of some degree of attention. Set in Lapland, Finland’s northernmost region, the film blends werewolf and vampire myths, dark magic, and human–animal transformation.

Samuel Johnson once said, “He who makes a beast of himself gets rid of the pain of being a man” — but Mirjami Kuosmanen’s Pirita isn’t a man. Married to Aslak (Kalervo Nissilä) and unhappy about his being being away for work so often, Pirita visits a shaman (Arvo Lehesmaa) in hopes of making her irresistible to the men around her. The shaman instructs her to sacrifice the first creature she comes across and she does so, killing a beautiful white reindeer. The love spell works, however, there is a catch: every full moon she transforms into a white reindeer and stalks the snowy landscape looking for blood to spill.

Blomberg is aware of the cinematic power that’s inherent to his snow-covered visuals — how many characters throughout film history have bled out and/or died lying in the snow, for instance? — and makes great use of their virginal associations when framing Pirita’s insatiable and sexually charged (in short, vampiric) appetite against it. This juxtaposition is extended by the figure of the titular white reindeer: its white coat and animal innocence lure men away from their wives, homes, or hunting parties only for them to be devoured by the shape-shifting seductress that lies in wait. Female desire is rarely rendered with this much poetry and menace.

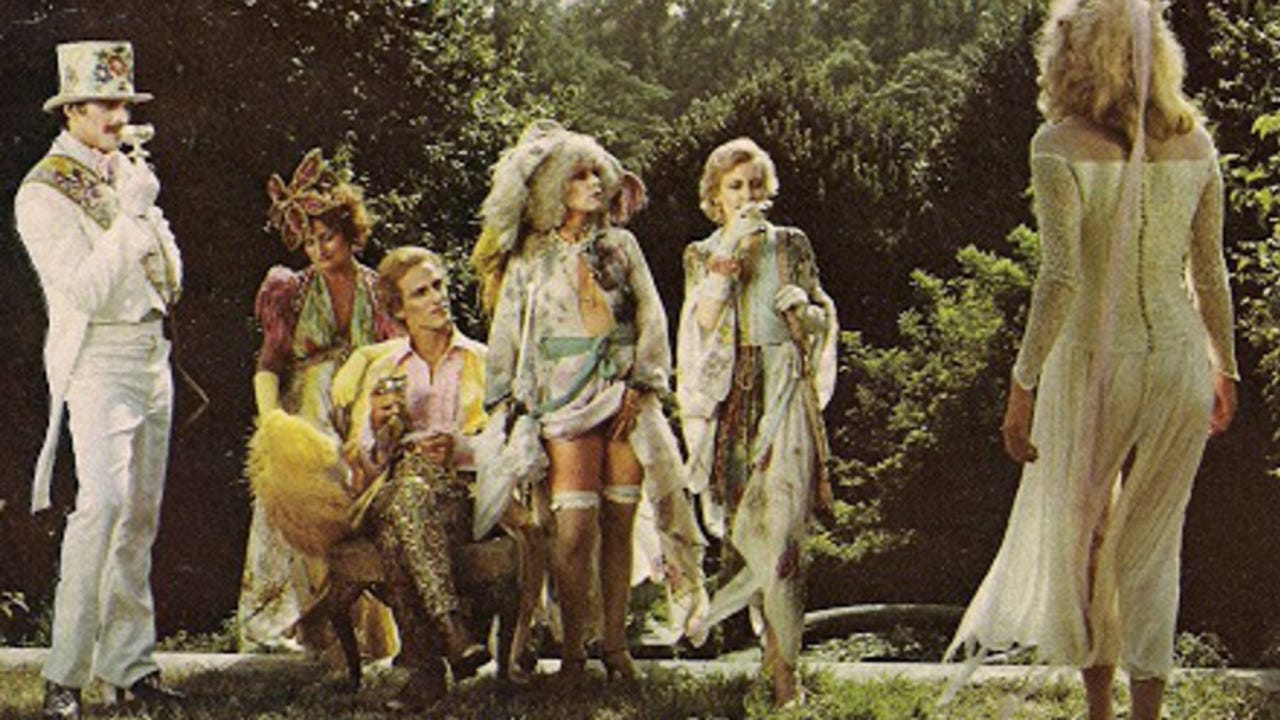

Through the Looking Glass (1976)

The Golden Age of Porn has been dead and gone for about forty years now and the idea that pornography could at one point be talked about publicly, discussed by writers and publications of some repute, not to mention referenced by television hosts, seems absurd now that the cultural conversation has seen a massive conservative shift that frequently takes aim at “unnecessary sex scenes” and has made accusations of “porn addiction” into a rhetorical weapon to be used on ideological opponents — we sure could use some of the French Decadent poets’ “épater la bourgeoisie” spirit right about now. But even during more permitting times, boundaries always need pushing and director Jonas Middleton answered the call with Through the Looking Glass, a hardcore porn/horror descent into a woman’s personal sex-trauma hell.

Catherine (Catharine Burgess), a socialite who’s as rich as she is unfulfilled by her upper-class existence and a love- and sexless marriage. She regularly takes refuge in the attic where she pleasures herself in front of a large mirror that evokes memories of her childhood and teenage years. During one such visit to the great, dark upstairs, she encounters what she believes is her father’s (Jamie Gillis) ghost in the gothic mirror. The ghost quickly gets to performing sex acts on the confused (but still aroused) Catherine and proceeds to pull her into the mirror where she witnesses an array of twisted sexual scenarios. The brief visit proves alluring to the bored Catherine: her father’s ghost, later revealed to be a demon, invites her to become a permanent resident in the mirror realm, an invite she accepts. But, of course, the offer isn’t what it seems and she finds herself trapped in an inferno filled with all kinds of venereal depravity.

Unlike other works of pornography with dramatic and/or avant-garde crossover appeal (think of Japan’s pink film industry which flourished in the early ‘60s and throughout the ‘70s), Through the Looking Glass’ doesn’t get its kicks by placing titillation in the midst of its horrible quasi-eroticism but rather an approach that writer (and first Electric Dreams guest contributor) Peter Raleigh described thusly: “What if Fire Walk With Me had full penetration?” Perhaps a little titillation would’ve complicated the events depicted here in a productive way but there is something to its sledgehammer nightmare sensibility too: phallic vegetables shoved up rectums, incestuous fellatio, and a startling shot of the camera traveling up Catherine’s vagina, featuring actual vaginoscopy footage. (And people complained about Blonde.) If this all sounds extremely off-putting, that’s because it is. It just so happens to also be an extremely effective bit of transgressive filmmaking that is worthy of being discussed alongside better known artsy smut such as LA Plays Itself (1972), Water Power (1976), and Café Flesh (1982).

Ogroff (1983)

Somewhere in the backwoods of France lives Ogroff (director N.G. Mount), a hermit donning a beanie and a mask fashioned out of a sliced open medicine ball. As a soldier, he took refuge in the woods during WWII (maybe? the timeline isn’t clear), never got word that the war ended, and slowly went insane from the isolation. Years, indeed, decades, later, his war-time readiness to kill has lead him to murder anyone unlucky enough to step foot in the woods that surround his tiny shack, be it man, woman, or child. However, after a family’s car breaks down close by, his murderous routine sets in motion a series of increasingly strange events.

Ogroff, also known as Mad Mutilator, sits somewhere between no-fi scuzz and avant-garde drone. The story, what little there is, doesn’t make a lick of sense and Mount instead mangles (or mutilates) the narrative, slicing it into a series of disconnected murders — the killing scenes feature some glorious shot-on-shiteo effects that look like someone stuffed sweaters and jeans with raw meat and doused them in pigs’ blood because knowing the neighborhood butcher is cheaper than getting the stage stuff — that nevertheless crescendo into a totally off-the-wall final stretch.

Mount’s Stink-O-Vision is reminiscent of homespun exploitation crap that was produced stateside around the time — 1975’s Criminally Insane (a.k.a. Crazy Fat Ethel) and 1984’s Black Devil Doll from Hell are, perhaps, the most well-known examples — but very few manage to tap into the primordial sleaze soup that Ogroff seems to have sprung from. (As if low-rent blood-‘n’-guts derangement isn’t enough, there is also a scene where Ogroff masturbates using his axe for some reason.) It’s a total disaster but not many movies can fall apart as wondrously as Ogroff does.

Loft (2005)

A film directed by the highly acclaimed, highly prolific Kiyoshi Kurosawa — 2024 has seen three of his films (including Chime) premiere, a truly Hongian feat — whose Cure (1997) and Pulse (2001) have both become oft-referenced (though rarely matched) cult favorites, isn’t the most likely candidate for this column but amongst his sizable and highly idiosyncratic filmography there are bound to be works that fly under the radar somewhat. In the case of 2005’s Loft it isn’t merely a lack of attention but also a consensus which places it firmly in the middle tier of Kurosawa’s oeuvre.

Considering, for one, the debt the J-horror genre owes Kurosawa — he shaped its look and feel as well as the anxieties that permeate it in a substantial way — and, for another, how much of his work is dedicated to prodding or outright blowing up its framework, it’s quite interesting to see the ways in which Loft colors inside the lines, how much it operates within the genre constraints he himself help put in place and was simultaneously, and somewhat paradoxically, always busy subverting. (A second glance reveals this to not be a paradox at all; think of the revisionism that was baked into the Western genre from its very inception, before the emergence of “revisionist Westerns.”)

Loft finds his subversive gestures a bit more muted but it is interesting to see his off-kilter instincts play against a more conventional structure. And either way, even a more subdued Kurosawa film packs a wallop: the story of a novelist (Miki Nakatani, who also starred in the 1998 J-horror classic Ringu) who retreats to a quiet house in the suburbs which is haunted by a ghost that appears to be connected to a mummy her archeologist neighbor (Etsushi Toyokawa) recently discovered, is, in typical Kurosawa fashion, loaded with striking, haunting images, and a palpable sense of sadness. But most importantly, the film, as his work usually does, leaves us with a lingering question: is there any director working today who can capture decay the way Kurosawa can?

Hell yes! More Hardcore Halloween porn??? Who woulda thought!

Great reviews!!