I Can Almost See the Core

On Tobe Hooper's 'Spontaneous Combustion' (1989), the nuclear family, and modernity's terrible hidden structures

Even amongst defenders of his later work, Tobe Hooper’s 2000 animal horror film Crocodile is generally considered to be one of his weaker efforts (if not his weakest), though the reasons for this distinction vary. Contemporaneous reviews tended to single out the unlikable characters, the tin-eared dialogue, and the horrid CGI animal for ridicule but these relative nitpicks missed the crucial ways in which it diverged from Hooper’s otherwise artistically, philosophically, and politically sturdy body of work. While Crocodile makes some kind of sense as a Y2K-era update of his most famous creation, 1974’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre — it’s a comparison the Texan filmmaker has invited himself, saying, “It’s the 25th anniversary of the first Chain Saw, and I really wanted to create an atmosphere that will wind you up like that.” — with its suburban kids that get lost in the sticks only to come face to face with the kind of primitive violence that their sheltered middle-class existence usually shields them from, closer examination paints a different picture.

Like many horror films of its era, the premise is simple: a bunch of hard-partying, sex-crazed, obnoxious, moronic, and badly-dressed teens head to a remote lake in Southern California for a weekend spring break boat trip. While there, they hear a story about a large Nile crocodile named Flat Dog that lurks in the waters after having been brought there by an eccentric hotel owner who believed her to be an avatar of the ancient Egyptian crocodile-faced deity Sobek. The local legend turns out to be true when one of the kids comes across the crocodile’s nest and foolishly steals one of her eggs, hiding it in the backpack of one of his compatriots as a (severely misguided, as it turns out) prank. The already enraged croc mother-to-be — the rest of her eggs were destroyed by a pair of drunk fishermen — decides to hunt down and kill the teenagers until she gets her egg back.

This sets up the film’s primary dichotomy: while the kids feel painfully of their time, a crocodile is an ancient thing, a creature from prehistory that somehow exists right alongside them, alongside us. It does, however, also mark a departure from how Hooper tends to bring his characters face to face with the underbelly of modernity, the violence that permeates the “terrible structure behind the appearances of diversity and enterprise” as Thomas Pynchon calls it in Gravity’s Rainbow. In Crocodile, it is a metaphysical force coming after them and Hooper’s usual flair for perversity feels severely stifled by this framework.

Aside from making use of some disappointingly rote horror clichés — there’s the spooky local legend being relayed while sitting around a bonfire, complete with a fake-out jump scare to cap the tale off; there’s the curmudgeonly sheriff giving the protagonists sinister looks and vague warnings — the situation (and indeed the film itself) resolves as soon as its central issue is remedied and the normal order of things is reestablished so to speak. It’s all a bit abrupt — to be fair, a lot of Hooper’s later work is — but worse than that, it’s conventional. Three teenagers going about their lives after braving the challenges life threw at them — there is no indication of any deeper change within any of the survivors — is, perhaps, the furthest thing from what constitutes an ending worthy of its director, a director with a penchant for leaving his characters dead, disfigured, and/or severely traumatized, permanently altered in some way, by their experiences.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre saw its lone survivor, Sally (Marilyn Burns), laughing a maniacal and broken laugh in the back of a pickup truck after she barely escapes the hell she lived through in the Sawyer family house; in 1981’s The Funhouse, Amy (Elizabeth Berridge), having witnessed the death of her friends as well as that of the murderous Gunther (Wayne Doba), staggers out of the titular funhouse in a daze, her mascara runny and her cheeks red and puffy from crying all night — she’s even mocked by an animatronic fat lady towering over her — and shrinks in size as the camera pulls away, making her vanish against the vastness of the traveling carnival; after Caroline Williams’ Stretch kills Chop Top (Bill Moseley) in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (1986) she mimics Leatherface’s bizarre chainsaw dance that closes out the first film, her person having seemingly been taken over by the violence she just witnessed.

It’s more than just them bearing witness to violence, however. The events of Hooper’s films fundamentally change his characters because they grant them a glimpse behind the curtain, a look at things they aren’t supposed to see and, like the graduate student Danforth in H.P. Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness or the cabin boy Pip in Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, it causes a rupture in their minds that is severe enough to drive them mad. There are countless films renowned for their depictions of murder and bloodshed but what sets Hooper’s filmography apart, aside from the fact that his propensity for violence is regularly overstated, is the political heft the filmmaker imbues it with.

Audiences and critics tend to view the violence in Hooper’s film as a kind of aberration, a thing that lurks in the margins of society without ever meaningfully interacting with it. But instead of a break with the established order, the shock of what his characters experience comes from being confronted with the true nature of the order itself. Chain Saw’s cannibal family isn’t a parody of the nuclear family but rather the nuclear family distilled to its essence, a social context where violence emanates from rather than forming a refuge from it. The sequel drives this point home even more clearly, when it depicts Drayton (Jim Siedow), the cannibal family patriarch, as a well-liked part of the local community who just won the Texas/Omaha Chili Cookoff twice in a row by serving the unsuspecting judges human flesh.

1995’s The Mangler, Hooper’s most politically blunt film, essentially makes the economic structure of industrial capitalism itself the villain, so when the laundry-folding machine that gives the film its title begins chomping at the workers, the main source of the horror is the sudden and brutal revelation of the system’s true nature above all else. For Hooper, evil is a force that permeates the very fabric of the modern world — this is something he shares in common with David Lynch but more on their connection later — a world that exists constantly in the shadow of death, destruction, and misery, one where even a post-war golden age and its ideal of the nuclear family merely provide cover for a barbaric reality or worse, constitute the barbaric reality themselves. Nothing can escape the shadow cast by capital, empire, or their enforcers in the military–industrial complex.

No work in Hooper’s oeuvre exemplifies this idea better than his 1989 sci-fi horror film Spontaneous Combustion. The film opens in 1955 in the underground bunker of a hydrogen bomb testing site located somewhere in the Nevada desert. Brian (Brian Bremer) and Peggy Bell (Stacy Edwards) are part of a shadowy military research program called Operation Samson that, supposedly, seeks to test the resilience of certain materials against the radiation of thermonuclear blasts. The young couple survive the explosion — newsreel footage shows them being celebrated as American heroes after the fact, with the voiceover calling them “America’s first nuclear family” — but the scientists and high-ranking military personnel involved with the operation soon learn that Peggy is pregnant. Though irritated, they decide against performing an abortion and once the baby, named David, is born — on the tenth anniversary of the U.S. military dropping Little Boy on Hiroshima — they run tests which, aside from a permanent but mild fever and a perfect-circle birthmark on the back of his hand, indicate that the child is in perfect health.

The familial tranquility proves to be short-lived when both Peggy and Brian, while sharing in their excitement about their newborn in the maternity ward — Brian brings along a musical merry-go-round as a gift for the child, ominously remarking, “Isn’t it amazing what they’re doing with plastic?” — die a horrible death when they suddenly and without explanation burst into flames; “SHC,” as Dr. Vandenmeer (legendary filmmaker André de Toth in an uncredited cameo), a scientist brought in to examine the couple’s remains, calls it. “Spontaneous human combustion.”

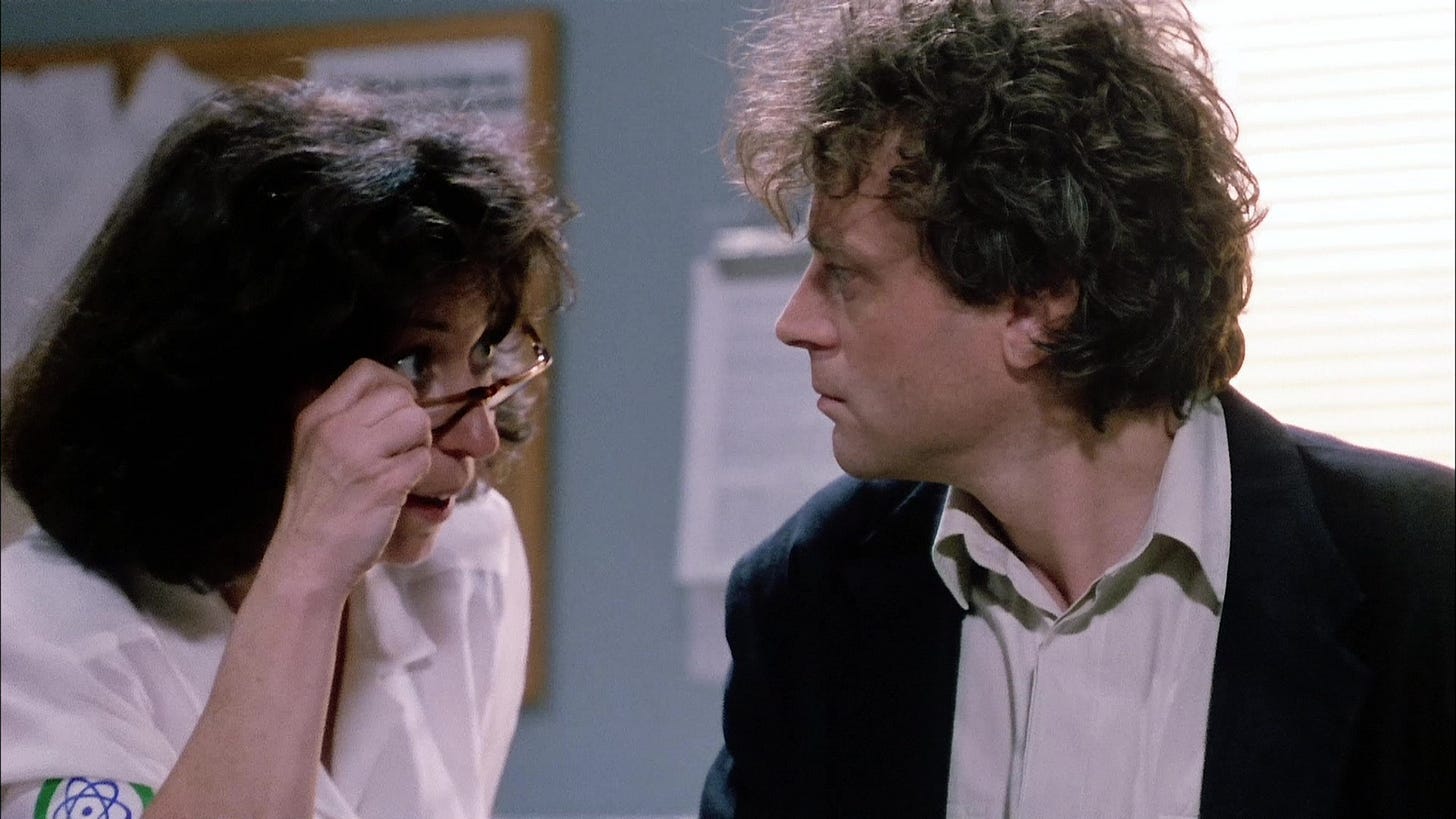

Three decades later, David (Brad Dourif), who survived the ordeal — Nina (Melinda Dillon), a sympathetic scientist, was holding him as his parents died their mysterious fiery deaths — and now goes by Sam, is a teacher at a high school in California with no knowledge of who his parents were or how they died. David is in a relationship with Lisa (Cynthia Bain) but aside from the permanent mild fever that has carried over from childhood, he also suffers frequent migraines for which he takes medication. After meeting his ex-wife Rachel (Dey Young) for a frustrating and humiliating lunch — not only is Rachel eating with Dr. Marsh (Jon Cypher) with whom she had an affair while they were married but she also sticks David with the bill — fire shoots out of his finger, leaving behind exposed and tender flesh. An appointment with the school physician, Dr. Simpson (Mark Roberts), proves only slightly less aggravating than the lunch and as an aggravated David goes to shake hands, he inadvertently shocks the doctor with a huge dose of static electricity.

What befalls David isn’t an unexpected mutation nor is he gifted superpowers with which he can mete out justice — it is the weight of a long political and familial history beginning to manifest in his body. It’s curious that Hooper worked closely with Steven Spielberg on 1982’s Poltergeist (his most famous film outside of Chain Saw, though often thought of as at least partially Spielberg’s achievement) since his accomplishments as a chronicler of the American family are overshadowed by those of his collaborator. What makes Hooper more captivating (and arguably superior), though, is the fact that his conception of the family unit doesn’t spring from a naive philosophical idealism but from the material-political realities that surround it. He understands the tectonic shifts of history and the way the atomic bomb (and the sophisticated weapons technology of the twentieth century, more broadly) was more than just a scientific breakthrough but rather the dawning of a new era, one where human annihilation was no longer only a matter of concern for God and the universe but for humanity itself.

What Spontaneous Combustion does is filter its family drama through these political realities or rather it is the political realities that give the family drama its contours in the first place. David, like most people, is completely unaware of the larger structures that have shaped his life from the very beginning. The film even connects micro- with macropolitical concerns by augmenting the story with a subplot regarding a nuclear power plant that is supposed to go online at midnight (the main narrative unfolds over the course of one day). Considering Hooper’s political sensibilities — he was part of a dying breed in the age of cynical disinformation hysteria and fact checkers: an old-school paranoid conspiracist; he even directed the first episode of the sci-fi UFO conspiracy television show Dark Skies in 1996 — these things (David’s family history, his strange abilities, his relationships, the United States military, the power plant, etc.) all end up being connected.

The truth unravels little by little, however, and David, bewildered by the strange occurrences, drives home only to experience a vision of his parents when he lights the fireplace and stares into the dancing flames. The ghosts of the past reach into the present: “I saw my mother and father,” he tells Lisa later. “They were trying to tell me something.” Paranoia and the paranormal, the irrational, run amok in Hooper’s vision of a society built on the moral ruins of World War II, its aftermath is still felt in the hum of everyday life.

In many of Hooper’s films, there is a sense that there are larger forces at work, operating just outside the purview of both the characters and the audience. Even a small-scale work like The Apartment Complex, a relatively light made-for-television mystery film he made in 1999, managed to evoke the askew claustrophobia of German expressionism (the building manager, played by Jon Polito, is even named Dr. Caligari) and Franz Kafka, as well as the kind of gnostic mystery fiction America is, or perhaps was, so good at. Hooper always had an acute awareness of the political forces behind the spectacle, behind the “events” that serve to roll out regime narratives but in Spontaneous Combustion these forces come into full view for the first time and with a clarity that he would not go back to for the remainder of his career.

Spontaneous Combustion has the blood of Robert Aldrich’s apocalyptic 1955 film noir Kiss Me Deadly coursing through its veins. Like Aldrich’s picture, it pushes its main character through a complex web of political and economic interests and both films trace the root of the modern world back to the atomic bomb. But Hooper’s tepidly-received — that might be putting it mildly given some critics’ rather intense dislike of the film — genre concoction is less intriguing for what it was inspired by as it is for what it ended up inspiring. The film embodies the nuclear family tragedy and repressed rage of Ang Lee’s similarly derided Hulk (2003) as much as it rivals the visceral power of the Trinity nuclear test’s birthing of a new evil in “Part 8” of Lynch’s Twin Peaks: The Return (2017).

Like the titular character of Lee’s comic book adaptation, David’s powers are beyond his control due to their sheer magnitude but also because they happen to erupt whenever he becomes agitated or angry. Bruce Banner’s (Eric Bana) dreams and fractured recollections of his childhood were brimming with the signifiers of the Atomic Age: doom towns, mushroom clouds, and a patriarchal inclination toward violence that hid under a veneer of respectability until it erupted with uncontrollable force, something which Bruce’s father, David Banner (Nick Nolte), knowingly passes on to his son as well, in more ways than one. Brian, Spontaneous Combustion’s central father figure, being kind and mild-mannered has no effect on where his son ultimately ends up, however — the long arms of power prove inescapable, regardless of how virtuous the individual caught in its fangs happens to be.

Trying to make sense of what is happening, David heads to Lisa’s apartment and she calls into a radio show hosted by the psychic Dr. Persons (Joe Mays), handing David the phone. He tells Persons about his visions and is suddenly able to recall his mother’s name as well as his own. Uttering the name his parents gave him causes a severe physical reaction, however, and his abilities overpower him, forcing him to his knees, causing the birthmark on his hand to double in size, and the line to disconnect.

In the midst of all this, his call attracts the attention of Nina who turned her back on her former employers after witnessing what happened to Brian and Peggy. She calls Persons’ show, pleading with David to get in touch with her. Already on the brink of losing control, David calls in again but only reaches an obnoxious, unhelpful radio technician (a regrettable and characteristically unlikable cameo by director John Landis). A furious David unwittingly sends a deadly charge of static electricity out the other end of the phone line, causing the technician to go up in flames.

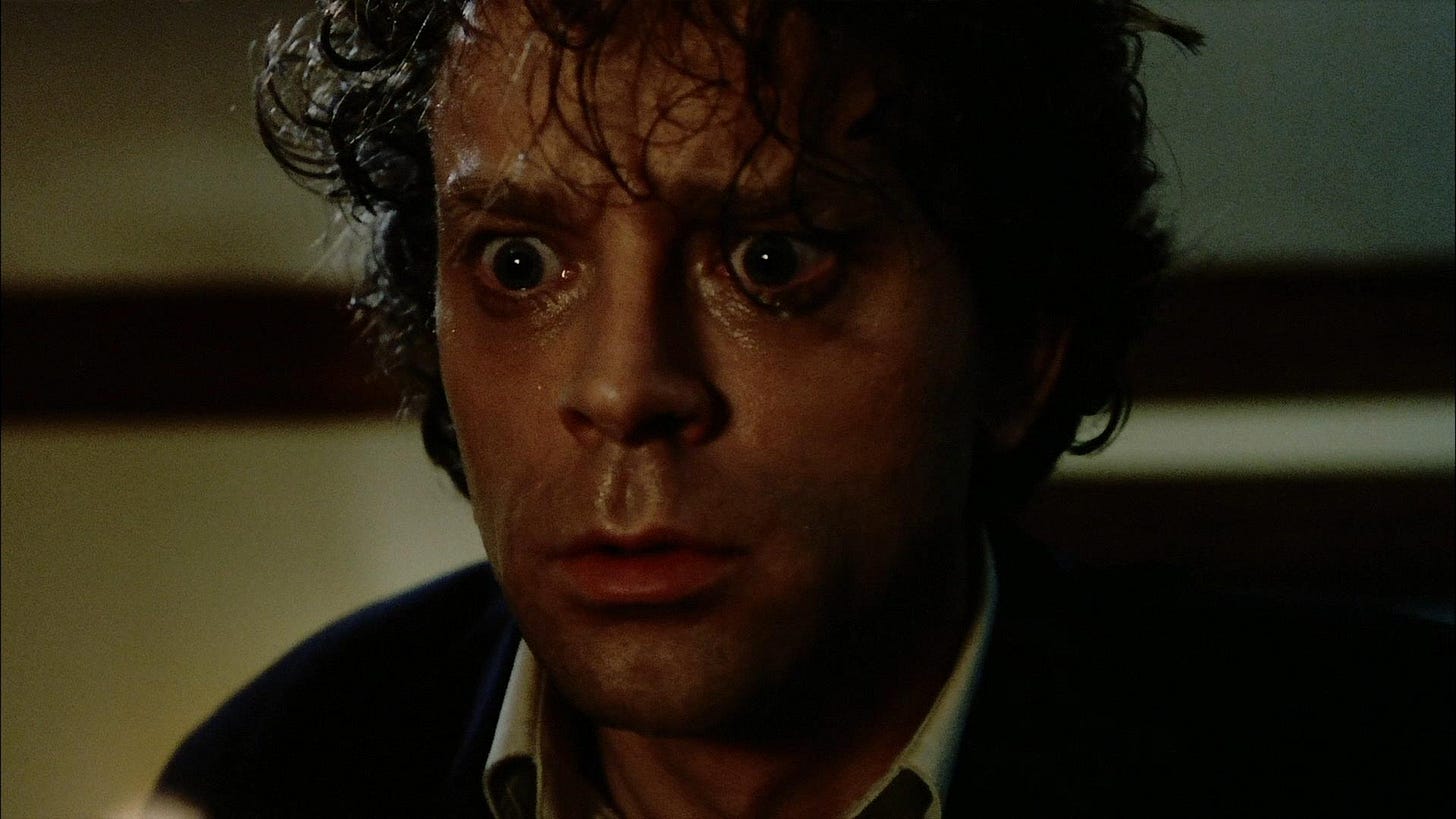

It’s a particularly forceful sequence in an incredibly forceful film. David has no idea just how much weight he has been carrying with him every day of his life (though the constant fever and the frequent migraines certainly suggested something was amiss) until all of it literally comes bursting, shooting, and oozing out of his body, devouring anyone who happens to stand in his way. However, what would otherwise mainly serve as a way to generate some genre thrills or simply to show off the effects work, is here permeated with a sense of profound tragedy.

There is a helplessness to the way the characters navigate their extraordinary circumstances both mentally and physically — mirroring the opaque goings-on, Hooper moves his actors through a labyrinth of angular corridors, examining rooms with sickly green walls, and strangely-lit living spaces — that is profoundly emotionally affecting. There are countless shots of tear-streaked faces, so many emotional confessions, so much heartbreaking confusion and anger; in fact, much of the film is just as ruthlessly overwhelming as The Texas Chain Saw Massacre even if it operates in a different emotional register.

After fire bursts out of his arm during the call, Lisa fills her bathtub with water but the water only seems to make it worse — “The water is like fuel,” she cries with tears in her eyes. “I don’t know what to do.” Later, while driving David to the hospital after the harrowing episode, he makes a confession to her: “I never realized it until today but my whole life I’ve been alone…Except, today when all this stuff started happening there was only one person that I really wanted to be close to.” But the despair soon overtakes him again: “I’m so scared,” he moans as fire shoots out of the hole in his arm.

Lisa, herself confused and emotional, reveals her own connection to the machinations that have governed David’s life. She tells him that Lew Orlander (William Prince), David’s wealthy former father-in-law, has been the one secretly pulling the strings, saying, “If it wasn’t for him we wouldn’t even know each other.” This doesn’t merely mark the point where David slowly comes to understand the omnipotence of the forces at work but also where the plot itself begins to disintegrate, a parallel to the escalating destructive power of his predicament. On his way to finally confront Lew directly, David lays waste to a doctor who attempts to inject him with a glowing green substance, two cops, and, tragically — accidentally — a sweet old security guard named Mr. Fitzpatrick (Dick Warlock), sadly looking on while he dies in agony.

By the time he enters Lew’s mansion — this set has an uncanniness that Hooper would go back to for 1993’s Night Terrors, an all but ignored curio that’s far more interesting and rewarding than its reputation suggests — David, in typical Hooper fashion, has been irrevocably marked by what has happened. What started with an injured finger tip has now turned him into a battered, charred, and bruised mess limping across the house’s chessboard floor. Unlike the majority of main characters in Hooper’s films, David is not only left psychologically damaged but visibly disfigured as well. His arc does deviate from those of his counterparts in another important way however: he is not the one who survives, Lisa is.

Through Lew, David finds out that Lisa has been burdened with the same abilities he has and that his underlings, namely Rachel and Dr. Marsh, are after her now that they are beginning to manifest. Though David seemingly dies when the nuclear reactor goes online and he explodes in a massive fireball, taking the wheelchair-bound Lew with him, he reappears to save her not just from her attackers but also from her condition. “Lisa, let me help,” he croaks, his face burned beyond recognition. “I can take your fire.” Flames erupt from her body but David gathers what’s left of his strength to rid her of this curse that’s been put on her, disintegrating as he does so. Significantly, he also rids her of the nasty wounds the flames left behind, leaving her previously severely burned forearm perfectly intact.

It’s appropriate that Hooper’s most empathetic film ends with a gesture of self-sacrifice but there remains a palpable loneliness to the final shot of Lisa staring dejectedly at the glowing crater where David stood just a few moments earlier. Hooper’s concerns lie with the human beings (and non-human animals) just as much as they lie with the shape of the horror he puts them through, if not more so. Spontaneous Combustion was released at the end of a decade which saw American horror retreat into farce — Larry Cohen and George A. Romero were some of the only horror directors who could match both Hopper’s intelligence and his gift for muscular genre filmmaking during the Reagan years — but Hooper’s film fought wildly against the current, raging against the dying of the light.