The following piece is the first in my monthly In Review series, where I take a look at more recent works. These posts are intended for paid subscribers only but in order to give people some sense of what it is I’m trying to do here — never mind the fact that Infinity Pool barely even qualifies as “recent” anymore — I’ve decided to make this first one available for everybody. Thank you for reading.

One can only speculate as to what moved Brandon Cronenberg, son of body horror pioneer David Cronenberg, to open his 2019 film Possessor with a police shooting of a Black woman. The film’s opening scene sees Holly (a memorable Gabrielle Graham) prepare for her shift as a caterer — which, in her case, seems to entail inserting a needle into her scalp, turning the dial on a strangely archaic device, and going through the entire range of human emotions while staring at herself in a mirror, laughing, sobbing. Later on, as she is making her way through a lavish party, she grabs a knife from a table and brutally stabs one of the party guests, oddly enthralled by the gushes of crimson blood pulsing out of the man’s thin neck wound.

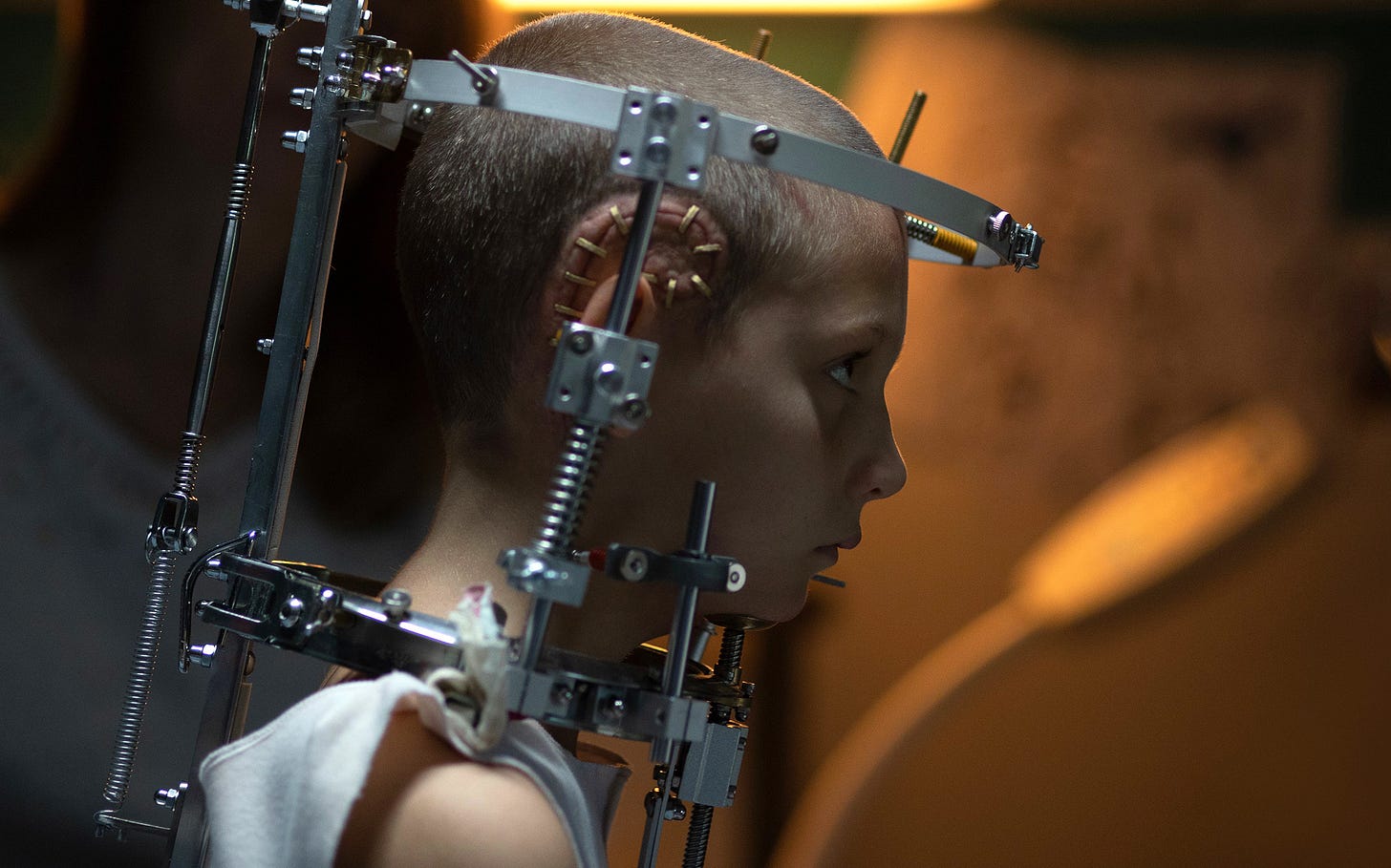

Snapping out of her daze, she pulls out a gun, puts it in her mouth, and prepares to pull the trigger. But as armed police rush into the dining hall, she suddenly hesitates, her face contorted in a desperate grimace which stands in stark contrast to the blind determination she had exhibited just moments before. Instead of dying by her own hand, she points her weapon at the police and is swiftly riddled with bullets, a final shot to the head sealing her fate. The scene cuts to Tasya Vos (Andrea Riseborough), gasping for air in a lab room somewhere far away. We learn that Vos is a corporate assassin who, with the help of stylishly retrofuturistic technology, inhabits people’s bodies to carry out her contracts, killing her vessel once the job is completed.

The film complicates this relatively straightforward conceit by having her hosts occasionally wrestle for control of their bodies, as was the case with Holly stopping her from pulling the fatal trigger, her basic human instinct for self-preservation bleeding through in spite of the extraordinary mental capacities which Vos supposedly, well, possesses.

It’s a prologue rife with subtext and loaded imagery. Released the year before worldwide protests erupted in response to the killing of George Floyd, Possessor’s shot of Holly’s silhouette being torn to shreds in a hail of gunfire is still potent and thorny, which is to say nothing of the eventual reveal that her actions were controlled by a white woman, who herself is shown to be a pawn in larger — though still overwhelmingly white — corporate structure.

But “subtext” is the operative word here: Cronenberg’s sophomore effort worked exactly because it forced its audience to sit with its ambiguities. It seemed like the world’s premier body horror nepo baby had enough faith in the evocative power of his images — and those of others as well, as the graphic headshot which concludes the scene, references Taxi Driver’s gritty brothel shootout — without having to resort to the kind of sledgehammer didacticism that has bogged down the works of his nu-horror peers, an unfortunate trend which (hopefully) reached its sad zenith with Alex Garland’s 2022 folk horror slog Men.

All of this makes Cronenberg’s decline on Infinity Pool even more disheartening. Gone is the cold, oppressive sterility of his cerebral (and thoroughly underrated) 2012 debut Antiviral, gone are the nasty genre indulgences and sly commentary on tech-induced societal decay of Possessor. In their stead, the filmmaker offers up shallow, self-satisfied social satire — of a piece with Ruben Östlund’s unbearably smug Triangle of Sadness — augmented by weirdly repressed sexuality.

The film follows James Foster (Alexander Skarsgård), an author battling a six-year case of writer’s block, vacationing at a luxurious resort in the fictional seaside country of Li Tolqa, with his wife Em (Cleopatra Coleman). The land surrounding the heavily guarded resort exudes a quiet menace, and the staff regularly reminds the guests not to venture beyond the gated compound. It’s clear that James and Em’s marriage has hit the skids, his struggle to create new work aggravated by a chronic lack of success and dependance on Em’s financial resources.

After the couple meet the mysterious Gabi (Mia Goth), supposedly a fan of the novel James has gotten published, James and Em decide to join her and her husband Alban (Jalil Lespert) for a trip to the beach — far away from the property they’ve been advised to stay on — where they spend the day eating food and getting drunk. As if the enigmatic Gabi’s motives weren’t inscrutable enough, she surprises James, who has excused himself to go urinate by a tree somewhere, with a handjob before wordlessly making her way back to the others, leaving a visibly shaken James behind.

The scene serves as an early indication of Cronenberg’s awkward prudishness. A far cry from the brazen sensuality that permeates his father’s work, Cronenberg the younger seems to regard sex — and female sexuality in particular — with an almost boyish disgust which belies his penchant for (sometimes superficially) transgressive imagery. During the first of many drug- or anesthesia-induced psychedelic sequences, he utilizes female nudity not to entice, not to critique but to shock, the woman’s stilted movements vaguely recalling Brigitte Helm’s maniacal, eerie dance in Fritz Lang’s 1927 sci-fi milestone Metropolis, though stripped of its unheimlich eroticism.

Li Tolqa itself, meanwhile, functions as a stand-in for a number of exotic, underdeveloped/overexploited vacation paradises for rich tourists. Those tourists tend to regard the country’s culture and customs, which include stringent religious conservatism and grotesque masks worn during yearly festivities, with a condescending bemusement, barely regarding the Li Tolqans — including those in uniform — as human.

When James accidentally hits and kills a local man while driving back from the beach, a darker side to the impoverished nation begins to emerge. He is arrested the next day and informed that the punishment for his crime is death, to be carried out by the man’s firstborn son. There is, however, a way for him to wriggle out of his harsh sentence: Li Tolqa has a system in place, whereby tourists and diplomats get to send a clone to their death in their place.

This privilege doesn’t come without a hefty price tag of course, but with the help of Em’s money and an arduous cloning process, his life is spared, and he watches the deceased’s young son repeatedly plunge a knife into his clone’s abdomen, the double begging to be spared until his last breath. The episode awakens a twisted desire in the glum James, this first taste of completely unchecked privilege unleashing an appetite for amoral debauchery.

After witnessing his double’s harrowing execution, the author falls in with a group of Western tourists who spend their annual trips to Li Tolqa abusing the resort staff by day, and gleefully committing horrific crimes by night. Once they are inevitably arrested, arrangements are made and they gather to watch their doubles be executed, all the while cheering like spectators at the Colosseum. As the film goes on, it becomes clear that the seemingly excessive resort security is just as much about keeping the guests in as it is about keeping the locals out.

The message is painfully obvious — Cronenberg’s third is his broadest yet. Never one for subtlety, his latest is nevertheless a shockingly one-dimensional philippic against our moneyed class. His thematic obsessions obviously invite comparisons to his legendary father but Brandon’s provocations align more with the showy visual filmmaking of edgy compeers like Gaspar Noé and Julia Ducournau than the considered and highly literate transgressions of his dad. Infinity Pool’s self-consciously trippy hallucinations — holdovers from his 2019 short film Please Speak Continuously and Describe Your Experiences as They Come to You — illustrate this point fairly well, their swarm of colors and wildly ostentatious editing succeeding at disorienting the audience, while not deepening the film’s psychosexual dimension. As with Noé and Ducournau, shock is king and, more often than not, exists for its own sake.

It’s similarly inviting to regard Infinity Pool — and all of Cronenberg’s oeuvre for that matter — as part of a cinematic lineage that goes back (at least) to Abel Ferrara’s hazy 1998 cyberpunk thriller New Rose Hotel, and found what is possibly its clearest expression in Olivier Assayas’ 2002 neo-noir Demonlover: information-age tales of human beings reduced to pawns in a slick, globalized, and corporatized world. Infinity Pool is perhaps less explicitly concerned with how the digital world affects the material one but it’s hard not to read the characters’ elitist disdain for the local culture as anything other than an outgrowth of neoliberal hegemony — to which the proliferation of Silicon Valley tech-ideology is inextricably tied.

But unlike Ferrera and Assayas, Cronenberg fails to offer any insight that goes beyond trite “eat the rich” gesticulation. Having earned laudits for Possessor’s political commentary — including its provocative opening sequence — the director seems to have bought into his own, admittedly well-deserved, hype. Consequently, he appears to fancy himself something of a truth teller, an uncompromising artist taking on the rich and powerful while exploring humanity’s ugliest impulses. In reality, it’s the stuff of a neutered, defanged J.G. Ballard story — think of Infinity Pool’s resort as the upper floors of High-Rise’s titular tower block — an author whose 1973 novel Crash was, incidentally, adapted by the elder Cronenberg in 1996, to far greater results. (Ironically, Brandon Cronenberg is set to write and direct an adaptation of Ballard’s Super-Cannes as a limited television series.)

The father-son connection is worth returning to since both Jr. and Sr. use their latest projects to reflect on their respective careers. At this point in his life, David Cronenberg has both feet planted firmly in his late period, and last year’s Crimes of the Future — easily 2022’s best film — saw him exploring his legacy with the kind of insulated, discoursive sensibility which is typical of late style works. His spawn, on the other hand, settles for a humiliating scene where Gabi — propelled into full-on queen bitch mode by the characteristically deranged Goth — reads bad (and badly written) reviews of James’ novel to him with a drunken sneer.

Further, Crimes’ setting — a crumbling, graffiti-covered semi-dystopia played by Athens, Greece — feels purposeful as an invocation of deteriorating cultural foundations. Conversely, Infinity Pool mainly uses the paint chip-covered halls found in Croatia and Hungary to create a sense of otherness that, unlike Possessor’s eerily anonymous alternate-history Toronto, feels trivial and doesn’t enhance the text in any meaningful way even as it adds some welcome texture to the the drab world.

Cronenberg’s urge to denigrate himself by degrading his main character — James is an obvious stand-in for the filmmaker — scan as dishonest since both Antiviral and Possessor have received largely positive reviews, the latter being hailed as one of 2019’s best (horror) films by more than a few outlets. (Also, there have been no calls for any of his films’ banning, unlike what happened with his father’s adaptation of Crash.) Infinity Pool itself has even won praise for its “bold” handling of themes and assured direction. But Cronenberg’s third faintly futuristic sci-fi shocker isn’t bold as much as it expertly signifies boldness through flashy, but ultimately hollow aesthetics. It’s clear that Cronenberg hasn’t lost his eye, but hopefully he’ll start using his brain again soon.

🔥🔥🔥