In Review: 'The Killer' (2023)

David Fincher's killer black comedy looks back and beyond

In light of the considerable weight his name carries these days, it’s easy to overlook the fact that David Fincher’s three-decade filmmaking career was not exactly a sure thing. After making a name for himself as a music video director he was given the keys to the Alien franchise’s third installment and immediately produced a critical and commercial flop with 1992’s Alien 3. However, it took him only three years to recover with Se7en, a suffocatingly bleak crime thriller that essentially defined what that kind of über-grim genre exercise would look and feel like for the next ten years or so. The director closed out the millennium with his most enduring creation, Fight Club (1999), adapted from Chuck Palahniuk’s novel of the same name.

With Fight Club, Fincher took aim at the gaping void at the heart of post-Cold War American consumer culture and the film earned its place as a cult classic and a fixture of college dorm walls, right alongside Pulp Fiction and Scarface. Remarkably, it has survived charges of nihilism, glorifying (male) violence, and intellectual pretension, making it through several societal sea changes with its reputation not only intact, but better than ever — occasional screeds by Hiroo Onoda-esque culture warriors notwithstanding.

Post-cult success, Fincher has been gliding through the 21st century with relative ease, avoiding disaster (Panic Room), teasing greatness (Gone Girl), and sometimes even achieving it (Zodiac). 2017 saw him enter a partnership with the streaming giant Netflix for his Mindhunter TV series, a partnership which has also produced 2020’s divisive Mank and now The Killer which follows a nameless assassin (Michael Fassbender) who, after a botched assignment leads to a brutal attack on his girlfriend, Magdalena (Sophie Charlotte), slips into the role of an avenging angel.

Fincher introduces his eponymous killer as a methodical, highly skilled professional, one whose interior monologue espouses a profoundly cold Weltanschauung. In between doing yoga, taking naps, and listening to the Smiths, he rattles off birth- and death rates as he rationalizes the glaring sinisterness at the heart of his chosen career path. But the affectless, quasi-philosophical voiceover that accompanies the overture (and makes up a majority of the film’s script) also reveals a man whose mind has been dulled by years of murderous monotony. Musing on his life philosophy, he quotes the famous axiom “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law,” espoused by famous British occultist Aleister Crowley but left ominously unattributed by screenwriter Andrew Kevin Walker: “To quote… someone. Can’t remember who.” Perhaps his mind was never all that sharp to begin with.

The illusion of infallible hyper-competence comes crashing down fully when, after days of preparation, he accidentally kills a dominatrix hired to entertain his intended target. Fleeing the scene in a competent, though slightly inelegant, manner, he makes his way back to his hideout in the Dominican Republic which has been broken into and is marked by signs of a violent struggle. His lover, meanwhile, lies battered and bruised in a hospital bed. It is only then that the implications of his choking act become apparent to him and he sets off to find the people behind the attack — the very people who previously wrote his checks.

Readings of The Killer as a winking metacommentary on the Fincher protags of old — Fight Club’s charismatic hunk/terrorist Tyler Durden in particular — are perhaps inevitable but this is also Fincher in a slightly different mode, one that looks to both the icy, globetrotting thrillers of Olivier Assayas as well as his own filmography. Like Assayas’ 2000s neo-noirs Demonlover (2002) and Boarding Gate (2007), The Killer is mainly set in transient spaces such as airports, hotels, and parking garages, and while the former’s protagonist (an inscrutable Connie Nielsen) operates within the glossy world of corporate espionage, the latter’s anti-heroine (Asia Argento) has her feet firmly planted in the criminal underworld as well.

Contemporary audiences have come to view Fincher’s more incendiary works as thinly-veiled critiques of toxic masculinity and the patriarchy, imagining him laughing right alongside them, enlightened by the same unproblematic, straightforwardly progressive views they hold. (One is reminded of David Lynch’s supposed disdain for small-town America which is commonly — and falsely — inserted into readings of Twin Peaks.) It’s true that Fincher certainly doesn’t admire his violent male characters but, like Lynch, he doesn’t entirely detest his subjects either (I’d argue that no interesting filmmaker does).

Either way, these interpretations persist and as a result, the titular killer has been caricatured by many critics as something of a bumbling oaf, essentially an open challenge to the members of the audience who idolized Tyler Durden or any of the “literally me” characters that have graced screens both silver and televisual. (They’re not quite as eager to discourage audiences from deifying Gone Girl’s Amy Dunne.) Puzzling, given that, with the exception of the opening hit (which only narrowly goes wrong), he is portrayed as fairly competent or, at the very least, perfectly capable of achieving his goals. Rather, the crux of The Killer’s death-industry character deconstruction (for lack of a better word) comes from our privileged access to his thoughts.

The unceasing monologue is exactly where Walker’s script shines as it contextualizes both the killer’s successes and his failures. A good chunk of the film’s comedy emerges, often somewhat unassumingly, from the discrepancy between his cold-blooded elite hitman ruminations and how things play out in practice. In an attempt to torture information out of his handler, Hodges (Charles Parnell), he uses a nail gun to drive three nails — as good a time as any to mention that Nine Inch Nails members Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross composed the film’s score — into his chest. But just as the assassin begins running the numbers in his head (“Three nine-gauge nails. Early middle-aged nonsmoker. About 180 pounds. Should last six, seven minutes.”), his voiceover flat with professional remove, he looks on in a slight panic as Hodges shuffles off this mortal coil in mere seconds.

It’s not the only time his mantra of “Stick to the plan. Anticipate, don’t improvise” is reduced to farce and he finds himself having to improvise a new approach — nonetheless repeating the phrase in his head over and over. Locating one of the people who attacked his girlfriend, he is caught off guard by the hulking goon and forced to square off with this physically superior adversary. These are hardly evidence of his incompetence, however, since, even with all the hiccups, he still manages to accomplish exactly what he sets out to do: he not only gets the info he initially wanted out of his former boss by other means but also bests the imposing rival assassin in hand-to-hand combat.

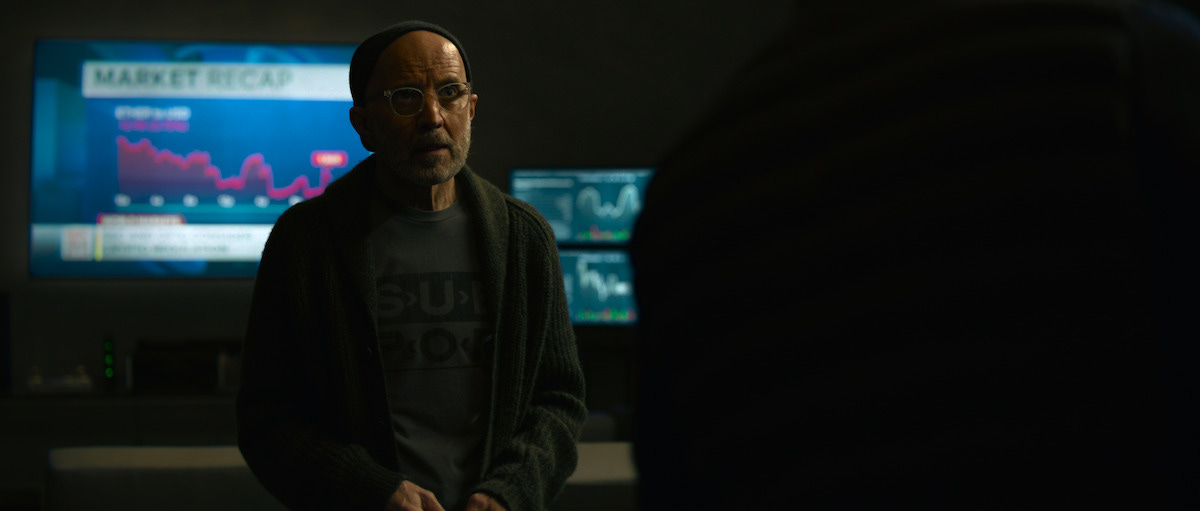

But the film is just as interested in the world its central gun-for-hire navigates as it is in the character himself. The Killer takes Assayas’ approach and runs with it by not only setting its low-key rampage against a backdrop of anonymous postmodernity — a landscape of fluorescent lights and tech-adjacent brand names — but also letting the corporate behemoths that pepper the scenery factor into the plot: at one point, the killer, facing a dead end, simply orders a doohickey from Amazon to clone a keycard he swipes off a janitor. Problem solved. (The Amazon app popping up on screen happens to be one of the film’s most effortlessly funny moments.) It’s probably not a coincidence that Sub Pop, the legendary Seattle record label and only recognizable “brand” to signify anything besides mindless consumerism, ends up on the t-shirt of a hapless billionaire — a commodity, stripped of any countercultural significance and authenticity it may have once had.

Fincher harnesses his Gen-X style of subversive irony — a concept that seems almost quaint in an age where power has embraced it so enthusiastically — not to dissect Fassbender’s character but rather the ludicrousness of his self-image and supposed code while operating as just another cog in the machine. He rents cars, flies economy, checks his Fitbit, sleeps in spartan hotel rooms, and eats at McDonald’s (while being mindful of his carbohydrate intake). This is what the story of a man driven by revenge looks like in the 21st century: an endless procession of commercial spaces, waiting in line, staving off boredom. Whether or not he’s actually good at his job is entirely inconsequential because, for all his pontificating, he’s just as much of a working stiff as everyone else trying to survive the gig economy — “the same decaying organic matter as everything else.”