The Image Is the Feeling It Creates

A conversation about Francis Ford Coppola's 'Megalopolis' (2024), rewriting the canon, auteurism, and the future of cinema

Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis made headline after headline prior to and immediately following its September theatrical release only for it to be met with mixed and often bewildered reactions from critics and audiences. My own feelings aside (I did not like it), it was clear that this was a work worth discussing, which is why I reached out to Alex and asked him if he would be interested in letting me pick his brain.

I was very proud to feature Alex’s fantastic piece on The Zone of Interest (2023) and Caché (2005) earlier this year and anyone who has read this or any of his writing knows that he has a remarkably sharp critical mind and a real knack for coming at a text from unique, unconventional, invigorating (but never thoughtless) angles.

I spoke with Alex on October 6, 2024 via Zoom and as these things usually go, we ended up speaking about a wide range of topics, including tech utopianism, dealing with problematic artists, the politics of filmmaking, and the state (and future) of film and film criticism.

Fred Barrett: The first question, obviously, what did you think of Megalopolis?

Alex: My immediate reaction is, it’s stunning. I think it lived up to the pitch from some of the trailers that it was going to be this maximalist, hyperdigital, super indulgent thing beamed straight from Coppola’s brain. But beyond that, I was a little surprised at how much of it was him sort of just straightforwardly articulating a vision — I expected it to be more of a character-driven thing. I didn’t think it would be something as… what’t the correct word for this? It’s a political movie, a political allegory. The film does essentially feel like him speed-running through his thoughts on politics, his thoughts on art, his thoughts on the intersection between those things.

A lot of people have said it’s a rather scatterbrained but I was actually surprised at how straightforward and cohesive it was, considering all the wackiness. Everything fit together very nicely. I also saw people say it’s “half-baked.” I don’t think that’s true either. I was actually surprised at how much it pulled from existing things that I was familiar with. I know a lot of critics have pointed to the references but I was struck by how thought out and clear the narrative was. I think that aspect of it pairs well with how it approaches its political ideas — there’s not a lot of subtext to read into. “Here’s what I think of the #metoo movement. Here’s what I think of urban development. This is what I think of technocrats.” And it’s almost concise with how it deals with a lot of those things.

You already brought up a lot of stuff I wanted to get into but I do want to lean into the politics a bit. You describe it as a political movie which isn’t what everyone read it as and definitely not what everyone was expecting.

I think there’s a lot of political agency, yeah. It’s not quietly political. Leading up to the release, many critics claimed that Megalopolis is Coppola talking about himself and his work as a director, which, yes, it is — he obviously thinks of himself as Caesar [Catilina, played by Adam Driver] — but I was shocked that it is less about art as a thing that’s removed from politics. This isn’t 8½, although I think the Fellini comparisons are apt. But 8½ is very much about art in a vacuum and about Fellini feels as a filmmaker. That’s not what Megalopolis is. Megalopolis is very much in communication with the world and things that are going on right now. Coppola says he worked on this film for twenty years or has at least had the idea cooking for that long and you can sense that this is something two decades in the making but also that there are things that only entered his consciousness in the past three or four years.

But with regard to how it deals with art, him making his artistic avatar an architect is very telling. Filmmaker don’t always like to be filmmaker in their movies. They’ll often say, “I’m gonna be a painter” or “I’m gonna be theater director.” I think him choosing an architect, someone who operates at that intersection between politics and design, an intersection that determines where we live, where we do government business in the first place, is a very deliberate choice by him.

Making a character an architect always seemed like a middle ground to communicate a their creative ambition without having to turn them into a bohemian. In 500 Days of Summer, Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s character works at a greeting card company which is depicted as soul-crushing but his ambition is basically just swapping one straight job for another. [Laughs]

[Laughs] No, absolutely.

But to stick with the politics — and this is not to be reductive — do you think there is some utility to the political vision that’s being presented here? Can we actually look to this for ideas of what a collective political future could look like or is it just this solipsistic thing that happens to brush up against these political ideas?

Well, that’s the interesting thing: I think it’s both. It is obviously very solipsistic but it also has this optimism to it and I’m fascinated by where he places this optimism. The opening of the film has Caesar demolishing project housing and then there’s this really interesting set piece where we’re in a kind of planning space with Caesar and Giancarlo Esposito’s character, Mayor Cicero. They’re there, debating what to do with the demolished projects and Cicero says things like “We need education. We need healthcare. We need places to live. This is what people need” but Caesar just dismisses him. “I’m thinking about the future.” But what is “the future?” It’s this nebulous, abstract thing. I think it fits very well with the technocrats we have now. They talk about the future but they don’t talk about people’s material needs. Those concerns are either explicitly or implicitly dismissed in this pursuit of a future that supposedly going to help everyone.

But even in that conversation between Caesar and Cicero, Cicero raises these points but all he cares about is building a huge casino. So even his retort to Caesar’s ideas is hollow. “You’re not thinking of people’s needs!” Well, neither is he. [Laughs] So there’s this interesting thing happening where the film is very much about these rich and powerful jostling for control, contrasting ideas about what the future of humanity will be while most of the people in the world, or the city, are cut out from this conversation.

I agree that the film is very earnest. I think Coppola is being extremely sincere and I think is trying to inspire conversations about art and society and things of that nature. But the film is also captive to how he views the world and in his mind these conversations are to be had by the most powerful, successful people. It’s such a shallow way to view the world — there’s no humanity in that vision. He reveals the hollowness of that idea without fully realizing it. I’m sure he’s aware of it to some extent since it is this fall of Rome allegory about America being in turmoil. Some of those things are baked in. But you look at Caesar’s designs and you have to wonder, “Where’s the utilitarian aspect of it? How does this help people get a meal? How does it give them easier access to fresh ingredients?” He wants to build this beautiful future society but it doesn’t have much use for people.

One bit of technology in Megalopolis, the city, that stuck out to me were these people-movers the sidewalks are equipped with. People can stand on them and they will take them places they could get to faster by simply walking. That’s one of the things our technocrats are good at: inventing worse versions of things that already exist. It’s like Tesla tunnels. [Laughs]

Just making those airport walkways look nicer and transplanting them to every sidewalk in the city. [Laughs] He wants to put them everywhere.

You can already stand on the sidewalk and wait to get taken places; it’s called taking the bus. Busses are, incidentally, nowhere to be found in this futuristic city. Instead, you stand on this weird shimmery, watery thing and can’t even sit down. It’s this really hokey kind of futurism that really gets into what you were saying about how people barely figure into Caesar’s vision. You could, of course, read all this as autocritique as so much art made by old white guys often is these days.

I think it definitely is to some degree. Caesar is his self-insert and Coppola has said he relates to him most of all. But I think this question gets into some of my problems with the conversation around Megalopolis, namely that viewing it through that lens feels limiting to me, in terms of how the film is actually functioning. It has a lot to say about creativity and how, by extension, Coppola feels about it. You can see the parallels: he wants to make these big, ambitious pictures and he’s been fought by studios his entire career and has to come to see them as an extension of bureaucracy. So all these things inform Megalopolis and you can’t dismiss them. So in that way, yes, it is a kind of autocritique. But it feels less pathological in the way it deals with all these characters. It’s like the film takes place outside their experience. It feels more satirical.

One thing I hardly saw at all when reading reviews was any contextualization of this film as part of Coppola’s 21st-century output. How does the scale and ambition of something like this square with Youth Without Youth, Tetro, or Twixt?

Actually, I haven’t seen Youth Without Youth or Twixt — I’ve been slouchy getting into that era of Coppola — but I think you said something interesting about Megalopolis on Twitter the other day: “A lot of it’s visually stunning, some of it’s moving but this doesn’t feel like the future of cinema.” I know you’re a big fan of the three films preceding this one so maybe you feel like him making a small movie like Tetro is closer to what the future of the medium could or should look like than this huge project. To me, this sort of contradiction is really fascinating because it’s a mirror of the contradiction within the film. Megalopolis wants to be this hopeful thing but inadvertently reveals that the dream itself is a little bit limited.

I remember that this film was pitched as this film that we need and obviously you can’t go into a film thinking that doesn’t mean anything. But at the end of the day, it’s just art. As important as it is, as much as a lot of us build our lives around it, it’s still just art. You can’t thrust that kind of responsibility on one film. Watching it, I thought, “This is great, this is visually sumptuous. A lot of it is unpleasant but unpleasant in interesting ways.” But I don’t know if we “need” big, indulgent, $120 million projects. I don’t know that the film accomplishes that particular ambition. Say what you will about the compositions, about the use of superimposed images, about the dream stuff — I just don’t know if it’s this era-defining work. Then again, does it have to be?

I remember reading this recent Rolling Stone interview where Coppola basically characterized his work this century as him relearning how to make a film. I thought it was interesting because his post-Rainmaker trajectory has been him, in some way, starting his career all over again, doing a string of modest, low-budget stuff that culminates in this comparatively gargantuan project. What’s interesting, though, is that he does somewhat take his newly-developed sensibilities into the big-budget work even as he falls into certain patterns that you associate with a kind of late New Hollywood opus: nakedly ambitious, self-indulgent, grandiose.

One thing that did certainly carry over, though, were the cinematic references. Tetro is loaded with references to Powell and Pressburger, for instance, and Megalopolis obviously echoes Citizen Kane on a thematic level but Coppola also just puts the RKO radio tower logo in the film at one point. What do you think it points to with regard to what he’s trying to communicate at this stage of his career that his early impressions of the medium have begun bleeding into his work in such a literal way?

Yeah, that was the most interesting thing for me — and to be clear, this is really not a criticism because I love this stuff and think it should make a comeback in movies — how a film that is ostensibly about the future is busy looking back. I think part of it is just him being an old guy. That’s what old people do. He can stand on his pedestal and talk about how he’s reimagining cinema all he wants — he’s an old guy in love with the films that inspired him and that’s part of why he’s a great artist. I don’t think that limits him in any respect but it is interesting to see the degree to which he’s still a captive to that.

As much as I loved Killers of the Flower Moon and Kevin Costner’s Horizon and am anxiously awaiting Chapter 2, as much as I love all these big, late style epics where thinking seems to have been “We’re gonna do one more great big film the way we used to make great big films,” I think they’re all running into this issue where they can be inspiring in terms of how they were able to mount this vision. These are great films but none of them have found a way of saying “This is the way forward.” Megalopolis struggles with this the most because of how it overtly positions itself as “the future.” Even the type of futurist Coppola imagines is this Elon Musk technocrat. It feels like something that would’ve made sense twenty years ago but now those guys are the villains. A lot of big, schlocky movies have villains that are technocrats or guys who want to invent an AI or something like that. A lot of us have realized the folly of following these people but Coppola is still married to that and I think that comes with age.

Some of these older guys really can’t wrap their heads around certain things. Coppola was talking about how he didn’t want this to be “some woke Hollywood production.” Paul Schrader, who’s like one of the few remaining filmmakers with some actual leftist convictions will talk about wokeness with regard to the Sight & Sound poll and is online constantly generating AI images. There is a certain disconnect there, it just doesn’t necessarily manifest in their work, at least not in the way you would expect it to. I can’t speak to Costner’s Horizon, that’s not really my bag.

Understandable. [Laughs] I mean, talk about hokey. That one’s extremely hokey. [Laughs]

[Laughs] So pretty much what I expected. But since you talked about the similarities, I do want to hear where you see the differences between Megalopolis and these other late-career epics? Killers of the Flower Moon, for instance, has a totally different energy to me.

Yeah, there’s not a lot that’s comparable on a narrative or formal level. The only real similarity is what they represent culturally but something I have been thinking about is the end of Killers of the Flower Moon where Scorsese seems to interrogate himself. “Has my project accomplished what I hoped it would? Can I give voice to this pain with my movies, these Hollywood movies, with entertainment?” We put all this prestige on Scorsese, he’s associated with pretentiousness for some, but he’s not an arthouse filmmaker. He’s an entertaining guy. He makes popcorn flicks. Very good popcorn flicks, very intelligent ones. That’s the meaning of the radio play, something that plays to a mass audience. That’s why he himself — speaking of filmmakers who don’t want to put themselves in their movies as filmmakers — does that reading at the end. Those are questions he’s asking himself.

What makes Coppola’s film so different is that there’s almost no questioning of Caesar, himself, by the end. Maybe throughout the picture but by the end he’s like “Everyone clear the way for the great technocrat, the great artist. Everyone move aside and utopia will be built.” That’s maybe why these contradictions carry a little bit more weight than if this had come from another filmmaker. A lot of these old guys do nothing but question themselves. Clint Eastwood has been making things like that for, what, thirty years now? [Laughs] He jumped into the aging director pool before anyone, while he was still a little too young to be doing stuff like that. Coppola, by contrast, is fully committed to being up his own ass in a way that is both eye-rolling but also kind of endearing. I think Megalopolis has both those qualities.

You don’t really hear about Scorsese as a political filmmaker or an ideological filmmaker and I don’t think he is necessarily but do you think that someone like him has more political intelligence than what Coppola brings to Megalopolis?

I think to a degree. I agree with the assessment that Scorsese is not the most political artist. He’s obviously not Godard in terms of articulating political ideas but I do think he gets down on himself harder than Coppola does. He interrogates himself — at least through film, I don’t know how much of that is happening in real life, of course. But this idea of questioning American morality is a throughline through Scorsese’s work, specifically in the context of people raised in the Catholic church, is a huge part of his movies. I think that leads him to be less naive about his role in things and that makes his pictures more relatable to me in terms of my own political beliefs. “There are things I should critique. I shouldn’t accept everything as dogma, whether that includes powerful people, spirituality, etc.” You can read a lot of political things into his films, even stuff he might not be aware of himself. There might be a better critical, political utility at times than with Coppola. That’s not to say Coppola hasn’t done that. Apocalypse Now has as ardent a political philosophy as any film. The Godfather too — these are relatively concise political films. But he also has films like Megalopolis which are more confused.

You mentioned the way Scorsese gets down on himself and I’m wondering if that’s maybe what the culture demands from these old-white-guy auteurs now. Do you think there’s a correlation between Scorsese’s acclaim and his willingness, or eagerness even, to cop to his own culpability, and on the flip side, between Coppola’s unwillingness to be apologetic for basically anything he’s said or done and the critical drubbing he’s received for his more recent work?

I think so, yes — to an extent. Coppola is an incredibly sincere filmmaker and I think with sincerity you have to drink your own Kool Aid a little bit. That’s what leads him to create beautiful films like One from the Heart. But the main difference there probably has more to do with industry stuff which I don’t really have that much insight to or can fully articulate. Scorsese had his fights with studios too but he’s more of a player. He likes to put stars in his movies and he likes to work within the confines of the studio system and make something like Gangs of New York or remake a film like he did with The Departed. He’s obviously very good at baking a lot of his creative ethos into those movies and I’m not saying he’s somehow less of a maverick who fights for his vision but Coppola, as soon as he had the money and resources was like “I wanna make films any way I want.”

I think that’s the main difference, really. Scorsese, even though he’s more self-critical, he does sort of see cinema in a traditional light. He feels that we have to save movie theaters, we have to save studio pictures. This probably why he likes Ari Aster. Aster, regardless of whether you like him, is making films within those confines and I think that’s what has been motivating Scorsese. He’s a traditionalist. He loves old Hollywood, he loves silent movies. He thinks that’s what cinema is and he wants to preserve that for the future. Weirdly, Megalopolis points in that direction too even though a lot of Coppola’s recent work has been about saying “Fuck all that. I wanna go out and do it my way and if studios wanna pick it up, great. If they don’t, I’m gonna go try and direct live cinema theater.” I don’t fully understand what was going on in that period but I suppose that’s where the question and answer part of Megalopolis came from. So yeah, I would say that’s the difference between them as filmmakers but also from a career standpoint, how they have adapted and how Hollywood has developed around them over the past few decades.

Obviously Coppola’s last three films have, in pretty concrete ways, pointed towards what he’s doing with Megalopolis but some of the stuff he put out in the ‘80s does that too. With Tucker there’s a big thematic overlap with Megalopolis as well as Coppola’s own career — a guy going up against the Big Three automobile manufacturers to create his “cars of the future” — but in Rumble Fish you can see a lot of that visual weirdness as well.

Rumble Fish is a very expressive movie and it almost seems uninterested in its own story. It’s just full of this expressiveness that does connect to Megalopolis in a lot of ways — it becomes almost like a visual poem. It’s like a music video.

Certain moments do feel like the videos John Landis was doing with Michael Jackson around that time. The scene I always remember is the big fight scene that ends with Mickey Rourke letting his motorcycle ride into a rival gang member. The bike and the guy do these big flips through the air. I saw a GIF of that moment recently and it’s ridiculous out of context.

[Laughs] It’s been a while since I’ve seen the film but I remember that moment well.

Okay, so we’ve talked about these guys not really being interested in or able to show us a way forward for cinema but do you think there are older filmmakers who are doing that?

I definitely think of Clint because I love how his recent run almost eschews dramatic intensity. There are dramatic premises but you watch them and they’re very, very gentle. Even in moments where it feels like things are going to explode, he finds a different way to resolve things. They’re so pared down, they very much live in the conversations between people. Another name that comes to mind is David Cronenberg whose age is also something we often talk about. He has an advantage, though, because his films are always about what’s next. And that question is scary. The old flesh is going to to die but the new flesh, which is scary and unpleasant in a lot of ways, is going to have things about it that you like, that are beautiful. That’s what Crimes of the Future is about. It’s about accepting the new ways in which things can shift. To me, that’s a film that’s truly engaged with the horrifying aspects but also the beauty and potential of change and I get a lot more out of that than what Coppola has articulated with Megalopolis.

Hong Sang-soo is getting up there as well and from what I’ve seen his recent films are all about making films in a new way even though he’s been making films that are antithetical to whatever else is going on almost his whole career, he’s still questioning that. I love that quote of his from when In Water came out where he said, “I’m tired of focus,” [laughs] which sounds funny, it sounds almost like a joke but then you see the film and he’s doing exceptional work. Seeing the lack of clarity almost feels like you’re looking at brushstrokes and then, of course, there’s the incredible ending.

So yes, there’s definitely older filmmakers questioning how films happen. What I don’t know how many of them are asking is, “Where is cinema going to happen?” I imagine things of that nature are interrogated in the avant-garde space but I don’t know that much about contemporary avant-garde filmmaking to make that assessment. But is cinema going to keep happening in movie theaters? Hong’s work speaks to that because most people aren’t seeing Hong in a theater. Those films don’t get heavily distributed — people are watching them as files on their computer. I’d love for the future of cinema to still happen in a movie theater but unless you live in a big coastal city, it seems like we’re going to have to let that go at some point. [Laughs]

What do you make of Tsai Ming-liang’s idea that film will be happening in art museums?

I think there is something to that. Now we’re getting into all the economic and political contradictions in Megalopolis. So much of art is connected with this stuff. Is there going to be a future for museums too? That’s the big question. When Tsai did his retrospective here in New York, I saw all those films in a museum and he showed his film Visage which is a collaboration he did with the Louvre and like most of his work it’s a masterpiece. Visage and his Walker films feel very much like museum pieces but they’re also fully cinema. I haven’t seen all of them but Abiding Nowhere, for example, is as good as any feature you’ll see this year. It’s one of my favorites.

But like I said, I think there’s something to what he said. There are going to have to be new spaces. Maybe it’s going to be a bunch of people getting together and getting $20 projector to project a film on a wall, you know? We all love our HD TVs and 4K discs if we can afford them but these are the kinds of things we might have to start thinking about: stepping back a bit in resolution so we can all enjoy something together as opposed to in isolation.

I think a question that inevitably comes up in all of this is the question of “What is the point of entry for filmmaking?” Asking what film is going to look like in the future is unavoidably asking that question as well. I was at the Filmfest here in Hamburg and saw a film called The Assessment. This was the director’s first feature, a pretty low-key thing, small cast, not a lot of different locations, and yet the budget was $15 million. I’m obviously happy she got to make her movie but how are these budgets going to be sustainable? Is the solution an amateur underground that could give rise to whatever the 21st-century equivalent of John Waters, James Robert Baker, or Nick Zedd is going to look like? How do you think people, working-class people in particular, can get their foot in the door?

I don’t think anybody knows but the big problem I have with how a lot of this discourse happens is whether it’s Tom Cruise or James Cameron or Coppola himself: all of it is top–down. The idea of a cinema that creates from the groundswell is never part of these conversations. And as much as I love Megalopolis for the weird beast that it is, I think it’s strange that the conversation revolves around it being more legitimate because he spent his own money. I saw someone say, “Spending $120 million on a film is the most moral good you can do.”

[Laughs] I’m not sure that’s true.

That’s ridiculous. It’s obviously not. He could’ve housed people with that money. I find it so interesting that that’s what people are coming away with. And in the film itself someone brings up the fact that people need housing and he dismisses it. It’s a very interesting film in that regard, very revealing. But when you go and watch foreign films, when you look at film history, you always find things that surprise you. I went to see some films of the Ousmane Sembène retrospective that happened here and if you look at Senegal when he got his start, there was no film industry to support his films. He found a way to make his own films but then he couldn’t do anything with them. Not because he was making films that wouldn’t make money — he was making films and there were no theaters.

He just went from town to town and showed his films. And his films, they’re political critiques, they’re comedies, there’s realism to them. He’s dabbled in a lot of different types of films and he just birthed the film industry practically out of nowhere. And to me, that’s kind of where we are now. Obviously, it’s not the same context, obviously the material conditions are different. But we should look to examples like that because that’s really inspiring. I think Tsai also just distributed tickets for Goodbye Dragon Inn on his own. He didn’t go to marketing. There’s a huge history of people birthing film where no avenues existed for them.

Going off that, I think the canon is something we also have to address as well. We can rewrite the canon and that might be part of shaping the future of film too. We make jokes about it, and I think people don’t take it very seriously but I do think, in general, the idea of doing revisionism is beneficial, overwhelmingly so. If someone can articulate a critique of someone like Paul W. S. Anderson or Michael Bay — I talk about Zack Snyder a lot — whoever, that is an instinct that’s very good. Now these are big filmmakers so it’s important we do it for the smaller guys too. Let’s talk about the guy who was using jump cuts the same year Godard was making Breathless. I’m not taking away anything from Breathless by saying that.

It’s just that film is so much bigger than what we think or feel consciously about. There are films in every decade, in every country that will blow your mind and have you thinking, “I didn’t know a film had done that before.” It’s just that we haven’t decided this 1970s film from India is worthy of being talked about in the same breath as a Bresson film. We need to reframe how we look at these things.

What I’m hearing is that you think a pink film needs to make the next Sight and Sound list.

Absolutely, yeah.

Good because, you know me, that’s what I was angling for.

[Laughs] A pink film should definitely be there. But that’s the thing. If we have any asset now that we didn’t have a while ago it’s that anyone can be an expert on anything: on pink films, on grindhouse films, on DIY filmmaking, on the avant-garde. The ability to go find that stuff is there for a lot of people. You find it and then you can become an advocate.

So if you were to give me, let’s say, five films that you think deserve to be considered as part of the canon, what would they be?

[Laughs] A nice on-the-spot question. [Pauses to think] Okay I already referenced this one so I’m going to say Koreyoshi Kurahara’s The Warped Ones. Came out the same year as Breathless. It’s a pulpy crime film, uglier than Breathless in a lot of ways, very high energy. The big difference is — and I don’t know too much about the production behind it — this one does feel like more of a studio film versus Godard who was making a film with wheelchairs on the street. But it does use a lot of techniques that we mainly attribute to European filmmakers. So that would be one.

That’s a good choice. I love that movie.

I also love Michael Snow’s Wavelength. A more talked about pick, I suppose, but that’s one of those films… all of cinema is in that movie. Julien Donkey-Boy is one. Early DV film should be talked about more. I think Julien Donkey-Boy takes so much from do-it-yourself video stuff and the people who were working with it before and eventually people like Michael Mann started to incorporate it into their bigger Hollywood productions.

Duvidha is another one, a really beautiful ghost story. Mani Kaul is as good as any director you will ever find. His images are so rich, the textures are so arresting. And the last one… [pauses to think] I have to include a silent film. I just watched a film called Ballet Mécanique by Fernand Léger and Dudley Murphy. It was made in the 1920s which is funny because we don’t really think of experimental film as being that old. When I was watching it I thought to myself, “Oh, these images have always been there. They were just waiting on a filmmaker to incorporate them.”

Those are fantastic picks. I was actually eyeing Duvidha for inclusion in an Electric Trio post.

I’d love to read your capsule on that. I’m starting to see more and more consciousness around Mani Kaul. I discovered him maybe two years ago and he’s one of the greats, absolutely.

To get back to Megalopolis, though, you briefly referenced a tweet about how making a film is the most ethical thing you can do with your money. Speaking of ethics, what do you make of the stories that were floating around about Coppola’s alleged on-set behavior? Did it complicate things for you at all?

Yes it did because it’s unfortunately in the film. It’s not separate at all. There’s that throughline. There’s the virgin character that is used in a plot to defame Caesar before it’s revealed that, wait, she’s not actually a virgin. It didn’t really make me think of the on-set behavior but it feels very much like Coppola’s addressing #metoo. Society builds up this ideal of the virgin woman, this pure woman that should be protected — it’s kind of sanctimonious. And there’s an interesting thing you could say with that but the direction he goes in is really unpleasant, which is that these women aren’t so pure and perfect after all so the shaming is basically okay. And then you look at Coppola and his relationship to Victor Salva and it’s hard not to see echoes with that sort of thing.

That’s the contradiction about Megalopolis, it’s what makes it such an interesting beast. I don’t want to say it’s an attraction because we shouldn’t place a positive value on these things just because they’re coming from Coppola. But it is interesting to see the parts where he is a prisoner of old-generation thinking. It’s baked into the film and that’s why you can acknowledge that it’s got many beautiful moments and it’s a great film while also admitting, “Yeah, its vision is a little fucked up in certain ways.” But that’s what you get when you go see a personal project like this.

How did you feel about him casting Shia LaBeouf? Shia’s someone I’ve written about at length but, surprisingly, I didn’t have that many thoughts on him being in this film by the time it came out.

Your piece on him was really good because I struggle with engaging this type of stuff in terms of talking about it and it gave a very clear emotional language to deal with those contradictions. It’s a beautiful, beautiful piece. The way Shia functions in this film is kind of interesting, especially since Coppola has him strung up like Mussolini at the end. I’m not saying that that’s Coppola intentionally engaging with how the public perceives him but it is curious. If I had to guess, I’d say Coppola doesn’t feel it’s his responsibility as an artist to be conscious of these things. But as an audience, we probably should be. Shia’s casting is a fact of the movie and it’s an unpleasant fact. And then you look at Coppola’s statements and he’s pretty clear about not paying any mind to what someone did or what conversations are happening. It’s another instance of him looking to the future and trying to be this progressive guy but also behaving in a way that’s pretty regressive. “In the old days, we didn’t think about this stuff.” That’s just filmmaking to some degree — you’re going to work with some bad people.

What’s funny is that people usually pay no mind to the men behind the curtain, the people filmmakers interface with to get their projects financed, for instance. We’re so focused on these individualized instances of bad behavior. Very bad behavior, admittedly but it’s also easy to point to someone like Shia and say, “This is a bad person and he shouldn’t be in the movie.” We don’t really talk about what it means for a director to be taking money from terrible institutions and people to fund their ultimately individualistic art projects or in Coppola’s case being the terrible financier himself.

But there’s another thing that was very revealing as well, which is how beholden people are to news cycles because Dustin Hoffman is in this movie and he’s been accused by multiple women of sexual misconduct and sexual assault. This pretty much flew under the radar. If it hasn’t been in the news the past few weeks or if the alleged victims aren’t famous, no one cares. Similarly, Shia was in Abel Ferrara’s Padre Pio which was a microscopic production compared to Megalopolis and there wasn’t much upheaval even though the consensus seemed to be that he shouldn’t be in movies anymore.

It comes down to the money, the platform. No one’s going to talk about him in a late style Abel Ferrara film. It’s about someone putting these people in front of our faces. And there’s another element too where we all agree that whatever Abel Ferrara touches is seedier. He deals in unpleasantness, that’s the attraction. He comes from the grindhouse. Obviously Megalopolis is just a movie people are gonna be paying attention to more. We had already given it this prestige before it even came out.

It goes back to the ways in which we view money, we view platforms, we view large stages as legitimizing. And we almost want that to be sanitized, we want we want our movie stars to be sanitized. We want everything to be. We tend to have a bigger revulsion than if it’s something that’s easier to ignore. It’s easier to ignore Padre Pio because how many theaters is that going to play in? How many people are even still watching his movies besides Ms .45 and and Bad Lieutenant? Even a lot of his fans are mainly fans of the early films.

I think the Ferrara project also had this element of “I’m helping out someone who needs it.” The way Shia ended up in that movie was through Willem Dafoe asking Ferrara if he could help him out. That feels like a different deal from him working with Coppola.

Something you’re definitely getting at here — and it’s a question that I’m not sure I have the answer to — is, what exactly are people’s objections? Is it the pathos objection? The willingness to work with this other person, to be in the room with this other person. Or is it purely about industry? Or is it both? Things like this can be revealing, you know? Even if you’re not making any money, just palling around with someone who has been “canceled.” It’s interesting to ask yourself this question.

It is interesting. Plus, Ferrera obviously has his own history with addiction and things like that so I assume he can empathize with Shia in that regard. He understands that people do fuck up their lives and those of others when they’re addicts.

I was going to mention Jodie Foster putting Mel Gibson in The Beaver too. I’ve defended some of Gibson’s films. I love Apocalypto. I know that we’ve talked about The Passion of the Christ being a very interesting artifact. But he’s a totally reprehensible individual. How can you make excuses for this? And then Jodie Foster makes this film, this family drama, this really bizarre movie that I did not totally hate. And there’s people getting up on stage saying he’s made amends. “He’s reformed. He’s apologized.” But how do you just make that type of mistake to say the things that he said? That has to be part of him to some degree. And obviously the defining fact of all these people is that they get these excuses because they’re rich and famous. Everything that happens in Hollywood is a magnification of stuff that happens at the lower levels all the time. But they are this insulated because they are famous.

Interestingly, Mel Gibson is someone who Shia LaBeouf pointed to when speaking about what gave him hope that he could face the world again.

That ties into a lot of people’s anxieties, understandably so, that this stuff does make a road map. Coppola’s relationship to Salva comes to mind again. He didn’t just defend him. He financed him, gave him a lifeboat. This is beyond someone defending their friend. He said, “I really believe in this guy’s movies and he deserves to have a career.” There’s a level of participation here which I think is different. It’s already hard to reconcile when you’re talk about people who are saying nice things about a friend of theirs and trying to clear a path for them to get big acting contracts again. But Coppola really put his money where his mouth is.

Is there a line for you? Is there a film you would under no circumstances watch because someone was involved in its production in some way?

I try to avoid stuff like that because we all reveal ourselves to be hypocrites. [Laughs] I try to engage with it in terms of an internal aspect but I’m not the biggest public advocate on stuff like this for this reason. I watch a lot of horrible stuff made by people who have done horrible things and I’ve already talked about those films in a loving way — I’ve already crossed the Rubicon. There are certain things, though: when these things are baked into the construction of the film, things being very exploitive. That’s when it becomes tough for me. A movie I have not seen despite being a Harmony Korine fan is Kids, for instance. Knowing what I know about Kids because of that documentary that was released a couple years ago, it’s a tougher movie to throw on. You can’t disconnect the film from the abuse.

Obviously, they’re not remotely similar, but by the same token, I’ll watch any number of films by Werner Herzog or whoever who is terrorizing their crew and committing all kinds of labor violations. I love The Revenant. Iñárritu was a bastard to his crew on that film. So I can’t really say that I have a line. It’s something I think about but it’s really something you just discover gradually through that process. And sometimes there’s no reasoning behind it. You try to put logic into it but I think we’re all hypocrites.

These feelings can also run up against the desire to experience something interesting. As an example, since we were speaking of Mel Gibson, the proposition of him leaning into this bad guy persona made Dragged Across Concrete irresistible to me. I could not wait to to watch it. There is an element of gawking to it as well, which interferes with the morality of it.

Absolutely. Sometimes I do want to see what all these labor violations resulted in. [Laughs] I think a lot of writers are becoming much better at tackling the idea of problematic people in movies. But often when the media takes on these stories, also with regard to Megalopolis, it feels like an advertisement for the movie and I think that’s why you saw some people very indignant, saying “This couldn’t have happened because of the salacious way it was reported on.” There was some journalistic weirdness in how they were talked about. At one time, people were complaining that Coppola would just sit in his trailer smoking weed and it delayed the production. Well, who cares? [Laughs] I don’t give a shit about that. Him going around and sexually harassing people, that’s a problem.

And then you had one woman who said he was totally fine around her and then another woman laying out the horrible things he supposedly did. And while there are critics who are good at evaluating through a retrospective lens, how to approach watching, for instance, Roman Polanski’s films, I think a lot of the reporting that was coming out on that was purely sensational. It felt like they were drumming up hype for Avatar. “Here are the water tanks.” There was definitely an unpleasant tenor and I think that allowed people to dismiss some of that stuff.

I forgot to ask you this before but I really want to hear your thoughts on this: what do you think it is about Salva’s films that Coppola likes so much?

I have no fucking idea. [Laughs] I couldn’t tell you. He’s obviously a weird guy. I haven’t seen the movie yet but I know he loves the second Joker. So he’s got weird tastes. I don’t know how to pathologize Coppola in this moment. It could come down to Salva’s legitimately a good friend and this is how he comes out for good buddies. I do think he’s a guy who watches a lot of films but how many current films is he watching? That’s why him and Scorsese and people like that develop these tastes. I don’t know if they have a Jia [Zhangke] drive and are running through all his films. Has Martin Scorsese seen Still Life? I have no idea. It could also just be that when you’re part of the old guard you feel like artists must be protected because artists are always under assault.

Which isn’t exactly untrue.

At least that’s how they envision themselves. [Laughs] In Megalopolis, the creative is the most persecuted person in the world. I find the way the working class is presented in that film so interesting, with Shia playing this Trump analog. Obviously, there’s some very coherent things there, like the false working-class prophet who comes from wealth and speaks to their anger while using them to facilitate his own insecurities — Coppola nails that stuff. But the working class are portrayed as a monolith, a monolith of sheep. Nothing comes from them in this picture and that fits right in with how the liberal media and the conservative media talk about the working class as this mob that just latches onto things. And of course nothing can come from them in terms of ingenuity, nothing can come from them in terms of creativity.

I’m trying not to make the mistake of saying, Trump’s base is just economically disenfranchised people. Obviously, there’s very real bigotry, xenophobia in this country that allows him to do that. But I do think Coppola’s view there is that all you need to win them over is just be that missing piece which plays into the megalomania fetish that he has. For him, good artists don’t emerge from the ranks of the working class who can then motivate and corral people. Unions or union movements aren’t happening. Protest movements aren’t happening within their ranks. The spirit of humanity, the spirit of solidarity will come from the top. It’ll come from someone taking it on themselves to be that voice. But that’s just not what’s happening. The working class is in a frenzy right now. You have a segment moving towards this xenophobic right but then you have labor movements, unionization all over the country and you have protest movements. They’re not just an energy resource, they’re people with a bunch of different circumstances, ideologies, coming together, being ripped apart and so on.

He was apparently mostly inspired by David Graeber’s work. Graeber has defensible positions but like so many of his anarchist brethren, he isn’t exactly the most rigorous thinker.

Yeah, when I talk about the politics of this movie I’m not necessarily making a value judgment but the politics are totally fair game if you're watching a movie where someone declares, “These are the things I believe.” I don’t like some of these things. I know there’s a lot of trepidation with how people talk about the politics of a movie these days because a lot of it is hack stuff. You can view these things and engage with the contradictions and allow yourself to feel something about the contradictions without defaulting to “Coppola made a piece of shit.” I think there’s repugnant stuff in there but that’s okay. I have people in my life who believe some repugnant things. Art is going be the same way sometimes.

There’s a lot of beautiful stuff in here. It does tug on your heartstrings in some very specific moments. It worked on me too. But we should also think about what it’s saying. Some people will go in and be like, “That’s exactly what I believe. Elon Musk is gonna build a rocket to Mars and he’s gonna give us wi-fi on every corner of the globe. And we just gotta let these guys take the reins and we’ll be in the new American era.” This movie is going to hit like catnip for those people. But if you don’t believe any of that the challenge becomes allowing yourself to engage with what the film is articulating in good faith.

Have you read a lot of reviews of the film?

I’ve read some but I’m going to take some time to dive into the reviews now that the blurb period is over. A lot of the stuff that was coming out was just… no. Again, the way people talked about this movie was all hype but now I feel like I can engage the reviews with a sober mind. I like to take time with a movie like this, to process it without reading somebody else’s thoughts. I am slow with that.

I was struck by just how little interesting writing a film like this inspired. What do you think the existence of this “take economy” says about contemporary criticism in general?

It’s tough because a film like this is almost always going to be a prisoner of all the lead-up to it, and that’s ultimately what a lot of the critique reflected. It was in a rush to either affirm or contradict the stuff we heard before the release. When I came out of the movie, I was thought, “Well, that wasn’t that weird.” It’s certainly different. It has idiosyncrasies. It’s very funny. It’s totally a personal project and, yes, it’s different than most things playing in the auditorium next door. These were the thoughts going on in my head but a lot of criticism was just about criticizing the hype. They criticized the taglines. That’s the measuring stick. And they don’t try to engage with what’s happening in the film itself. Even the question, “Is Megalopolis intentionally trying to be funny?” It makes me roll my eyes. How is this a debate? It’s so banal and trite to talk about it in that way. It’s obviously intentional. Driver saying, “Go back to the club,” that’s funny. I don’t understand what the debate is supposed to be, why we can’t allow movies to be funny in weird ways.

It’s a funny movie. Characters behave in interesting ways. And and then there’s moments in the movie that are more ambiguous. Why do you need someone to justify how that ambiguous moment plays? You get this when you watch really old movies. People will say lines stiff at certain points. They’ll move in a way that’s awkward. They were getting used to the idea of the camera being there and dialogue taking place. But anything that plays for 90 minutes or longer is going to have uneven patches and it’s remarkable that even cineastes who watch way too many movies and don’t go outside still don’t know how to engage with that part of movies. You don’t have to be in sync with every second of the film but that’s what a lot of these reviews seem to expect.

They aren’t even talking about the imagination of the film in an edifying way. It’s not particularly hard to see that Megalopolis is pulling from stuff in the silent era and yet I don’t see a lot of people bringing that up. I don’t think it’s particularly hard to see that it’s pulling from Citizen Kane. I don’t think it’s difficult to see that there’s Fellini and Sorrentino overtures in the film, although I’ve gotten a little bit of pushback on the Sorrentino comparison. But I think it’s there, particularly with Great Beauty. The ending is basically The Great Dictator which is super interesting. But really, it feels like people aren’t engaging with what the film is saying and they aren’t engaging with its images in any meaningful way. They’d rather complain about it being “indulgent.” What did you think a self-financed decades-in-the-works passion project was going to be? That’s not an observation. “The actors say stuff that’s weird.” I don’t need someone to tell me that in a critique. I’m going to see it myself and experience that. I don’t know if that answers your question.

Not really. [Laughs] But you did raise a lot of interesting points so it’s all good.

Fair enough. [Laughs]

I do find the “It’s indulgent” critique interesting, though, because it really doesn’t mean much when you’re talking about any auteur project. Tetro is no less indulgent. That’s what filmmaking is. “I have this idea in my head and now we’re gonna set up cameras and I’m gonna tell people to pretend to be another person so they can act out stuff that’s in my brain.” It’s hard to think of something that’s more indulgent. This is a reality we have to live with.

His pitch for the movie two years ago was, “I’m going to make a movie that inspires the future of humanity.” Well, if you weren’t prepared for something indulgent, I don’t know what to tell you. [Laughs] You had two years to work through that mental obstacle. That’s all on you. He warned you two years ago. You could’ve gotten over that months ago. If someone’s complaining about how indulgent it is, that’s their problem.

You also brought up intentionality and the very obvious observation to make is that if a film is good, if it’s shot really beautifully, people don’t tend to talk about intentionality at all even though it can be just as incidental as keeping a flubbed line in the final cut. But how much emphasis do you place on intentionality? Is that something you even think about? As you said a lot of moments in Megalopolis are obviously intentional but do you even care to begin with?

I do and I don’t. I like Megalopolis for reasons that I don’t think Coppola was intending. He obviously meant this to be a totally sincere work and it is. But, like I mentioned earlier, I also feel like it critiques his own thesis by revealing the holes in it. So intentionality only carries us so far. It’s a hard thing to articulate. You’re going to reveal yourself to be a hypocrite if you position yourself but I think the only coherent line of thinking is that films have their own language beyond the creator at a certain point. They do their own things. That’s what makes close readings so valuable. We talk about what the image means and how it relates to other films, how it relates to our culture, how these things can take on extraneous meaning. It’s the only way we know how to process this stuff. We try to inform it with as much context as possible, with auteur theory when applicable. But at a certain point you’re going to run into the question of, “Did the director mean to do this or for it to have this meaning?” What the image expresses is ultimately the most important part.

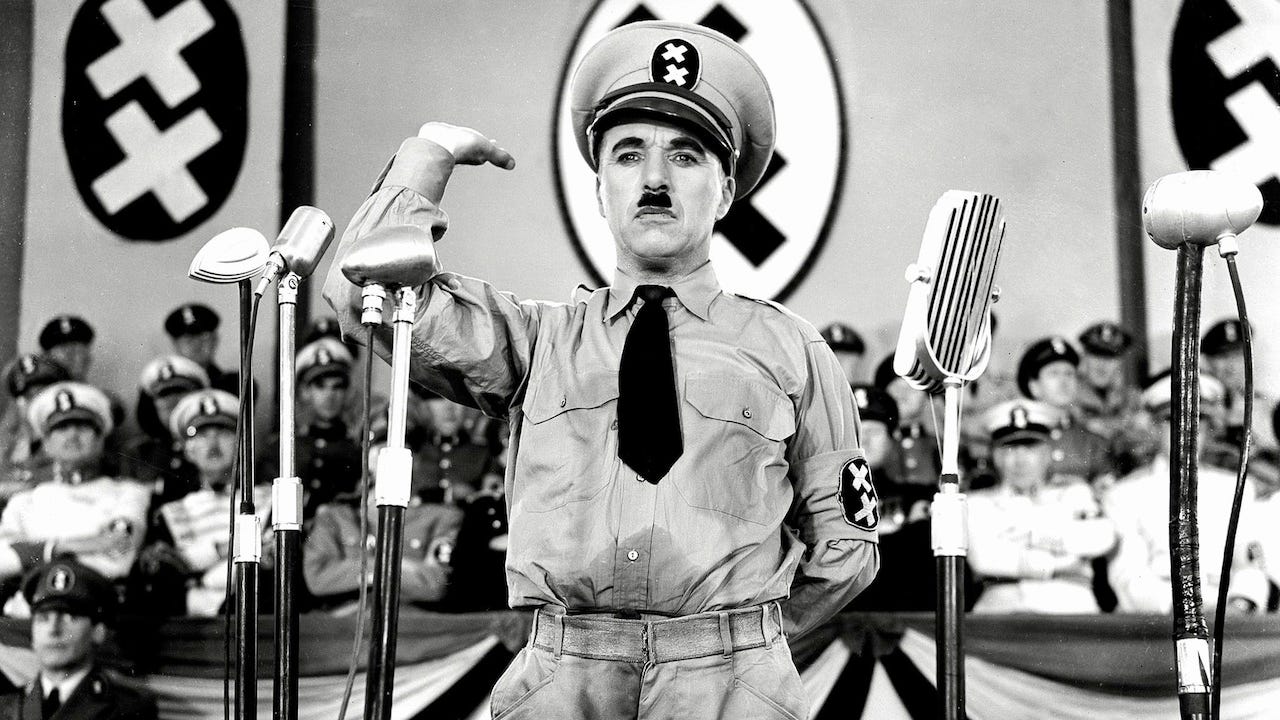

I mentioned it before but another film that is interesting in that regard is The Great Dictator. You have Charlie Chaplin dressed like Hitler and he stops the angry speech and he says, “Let us all unite.” He does that amazing speech you’ve probably seen on YouTube a million times. The intention of that scene is obviously him assuming Hitler’s identity and repurposing Hitler to talk about our shared humanity — that’s him getting his knives into Hitler. But the unintentional part of that scene which always chills me and makes me uncomfortable is the fact that that crowd, seconds ago, was still there to cheer Hitler. Those are Nazis applauding him. So he speaks about solidarity to people who are ostensibly fully committed to the Nazi cause. It’s supposed to be this healing moment but it’s just about a guy at the podium who can switch people like that. All he needs is a microphone. That is an extremely cynical observation about humanity but I don’t know that Chaplin intended for that movie to be so cynical but that’s what I get from that and I think that’s why The Great Dictator is a great film.

We do this with conservative art all the time. We do this with Michael Bay films where the the propaganda and the the pro-military aspect of them becomes noxious in a way that they can become critical of the American expansion project. There’s scenes in 13 Hours that are absolutely chilling if you’re engaged with this stuff at all. But when you do that, obviously, you’re never gonna have uniformity. Not every critic is going to see it. Not all audiences audiences are going to see it. There’s people who are more married to what the film is articulating on its surface than engaging with what’s quietly, accidentally being argued.

Do you think auteur theory is something that we might need to leave behind as we move forward?

I’m pretty much as committed an auteurist as you’ll find [laughs] so I don’t know. I like questioning it, though, because I think everything should be questioned. People have, I think, run away with it a little too much where it’s become this dogma but these things are just prisms. Everything is. Genre is a prism. Narrative is a prism. Art exists in a totally abstract space. We’re talking about impressions and feelings. You will go watch one movie that does one thing and another movie that does a very similar thing but you’ll hate one and you’ll love the other. And sometimes you’ll try to express it through cinematic language or narrative or your affinity for certain ideas but at a certain point you’re going to run into a situation where you can’t really explain why you liked it in one thing and why you didn’t like it in the other. That doesn’t devalue your opinion, that’s just what engaging with art is.

So it’s not that I think we have to leave auteur theory behind but we have to acknowledge these these things came away from trying to put words onto things that kind of defy being described in language. How do you talk about an image? Well, if you talk about a picture, it’s going to have less of an impact than the picture itself. Good criticism is a way to distill it but no one is going to understand the image better than when they go into a theater and they watch it themselves and they have their own ideas about it. I’m an auteurist, I like to see patterns in a filmmaker’s work and I like to talk about those patterns. For me it’s less about declaring the filmmaker the sole author of what’s going on. It’s more so a way to understand the communication that is happening through the art form. As long as people realize that these are just prisms, just tools, and there are right tool for the right jobs, it will be okay.

Lav Diaz said that criticism “broadens the limitations of art praxis…fulfills the vision through discourse, articulation, explanation, reading, interpretation, application, and scholarship.” He also described filmmakers and film critics as “comrades.” He puts criticism in this larger process of filmmaking or art making in general. Do you agree with that?

Absolutely. I can’t remember the quote exactly, but Radu Jude said something very similar about criticism as well. Scorsese talked about why he feels cinema is so important and why images are so important. He said images are incredibly influential and they’ve been tied to so much of our political and cultural history. The only way we can understand images is if we make films and get control over them and are able to more clearly see their power. We watch these films and try to understand how they influence things — criticism is our mode of doing that. It’s totally necessary.

We want films to speak for themselves but they can’t really do that. They speak to us and we have to decipher what they’re saying. There is no reason to obsess over the state of criticism if you don’t believe that to be true. You have to believe that this art form is important and that it intercedes with politics, culture, emotions, ideas. Film is our main dramatic output right now. It’s how most people grapple with being a human being in the 21st century. So yes, I think film without criticism would be much weaker and I think criticism can be anything from having a conversation with your friend to fully fleshed out, shot-by-shot evaluations of movies.

You mentioned “the image” a bunch of times. Well, images but also “the image.” What is the image?

Oh, Jesus. [Laughs] Well, that’s the question. I’m just going to take a quote from Godard. It was in, I believe, King Lear, where he said, “The image is the feeling it creates.” And that’s what the image is. I like that. I’ve read some film theory but I’m not the most well-read person but I’ve read [André] Bazin and people like that. I don’t have an encyclopedic knowledge but I do like that quote. The image is the feeling it creates. I think that opens up a lot of avenues into how to talk about some of this stuff.

So is it more of an emotional or more of a cerebral thing for you?

That definitely depends on the movie but I’ve also found myself thinking about how much both sides figure into how I personally respond to stuff. There are pictures that are just gorgeous but then I walk away feeling totally empty. I can see the composition element, I can see the lighting element, I can see how stunning the images are, and it still feels empty. And I ask myself, “How can something so beautifully composed leave me so cold?” And that’s where the interrogation comes into play.

We all think everything is pure emotion and that is often true. But I think sometimes we don’t realize how much we are actually thinking about something when we’re watching it. Our brains are doing something. We might not know what it is — I don’t know what my brain is doing half the time — but I’ve come around to the idea that there are very few things that are just pure emotional instinct. Something flipped that switch to make that emotional reaction happen. That’s why you read criticism because you will read someone’s words and think, “Oh, that’s why that shot did that to me. I didn’t know that someone else had the same idea.” That’s also when you realize that filmmakers are working on a very high level because they’re triggering that in multiple people.

This is something I’m working my way through with my own writing, this question of, “How do structure your writing or think about your writing and your ideas in an interesting way that either matches the film or plays off of it in productive ways?” Because when you write about a film like, say, Demonlover, a tech-heavy, 21st-century kind of thing, your vocabulary should to adapt to that. You can’t go about it the same way you would when talking about Ordet. There are these narrow expectations of what criticism should be but maybe the perfect way to talk about certain films is to write a poem. Maybe that’s the best way for your words to be illuminating.

I’m going to make use of another Godard quote, which goes, “The best criticism is to make another movie.” I like this idea: taking an image and saying, “It did one thing here and I can repurpose it.” If you make the antithesis of what was being argued before then you must have had a pretty good handle on what the original was saying. But with regard to writing criticism you’re definitely on to something. How we talk about pictures is a big problem. I complain about it but I always end up eating my words because when I do see people try to talk about them, I get annoyed with some of the things that are said. Everything is about story and character and narrative and world building. These are things that are very easy to talk about because there’s an almost mathematical quality to them. “A character did A because he believes B.” It’s all pathos and pop psychology. It’s a very rigid way of thinking — and it’s very easy. That stuff has certainly always been easiest for me.

By contrast, it’s very difficult to really talk about how a movie looks. I struggle with that all the time, both conversationally and whenever I’m writing. I find it brutal. [Laughs] But people need to be less afraid and just run with whatever comes at them because that’s what this is about. Films aren’t plays, they’re not books, they’re not anything else. They work because of what they’re putting in front of your face. It’s very simple. And when you realize that, it does become a little bit intimidating because the question becomes, “What am I even looking at? What does this look like?” And then you can try and probably fail to put some words onto that feeling.

For me it’s gotten to a point where I’ve started writing reviews on my phone, actually. Because, and maybe this is an impulse you’re familiar with, whenever I write a piece that’s over a thousand words this strange journalistic impulse kicks in where I feel like I need to say something about the production of a movie or I need to say something about the director’s previous work, I need to look up dates and things like that. But because looking stuff up on your phone is kind of a hassle I’ve noticed my writing becoming more unburdened by this impulse. I just open Google Docs on my phone and sometimes I’ll write half of a review sitting on the bus to work and finish it on the ride back home. Doing that has really opened my brain up in a lot of ways.

I wrote this essay on The Texas Chain Saw Massacre while riding the bus and during my lunch break and it was a huge deal for me because I felt like I was able to really push myself beyond these constraints. So thinking about writing differently also relates to how and where you write. Why do you have to sit down at a desk to even write in the first place? Brandon Streussnig mentioned on Twitter that he wrote his first reviews in a janitor’s closet. Sure, you never know if people are telling the truth but I certainly believe him.

Yeah, I always try to steal myself away from saying I write but I do like doing it because it’s like a road map for yourself. I’m not under the impression that people are actually interested in what I have to say when I post about movies on Twitter or write a Letterboxd review or send out a Substack piece or whatever. It’s purely for me. I want to understand what I’m thinking about something and sometimes the best way to do that is to just put it out there. That really teaches you how to think about the next thing you watch. And yes, a lot of times I’ve done this or even when it’s just putting stuff in the Notes app that I don’t put out anywhere is done when things are slow at work.

I like what you said about writing that Texas Chain Saw Massacre piece because I do wish more people would make that sort of pivot into talking about things in in a different way rather than the journalistic way. I love the dry stuff, obviously. I love reading these dry evaluations of what a film is doing. But so many reviews are tied into checking boxes. The critic should be put himself in there more. Doesn’t matter in what way, whether it’s dry or emotional or through personal anecdotes, whatever. You should be more of a voice than just rehashing things the way you learned to do them in school.

I remember noticing how I kept repeating this pattern unconsciously. “Here comes the second paragraph, better get to the plot description.” It was like I was on autopilot.

I used to write for my college paper and I was terrible. I was awful at it. [Laughs] I was very much cutting my teeth. But I remember running into problems because I would never want to talk about plot. I would just jump right into my thoughts and I hated trying to recall it, I hated trying to remember the sequential order of things. It drove me crazy. So I very much like that I can write something that’s largely unedited on Twitter or Letterboxd even though it’s probably totally unintelligible unless you’ve actually seen the movie. I just struggle with that stuff.

To be fair, that stuff can be good, it can be helpful, but we do need to loosen our expectations for these kinds of things a little bit if we want to keep things interesting.

I agree.

Okay, I have one last question I wanted to ask you. We were talking about the image a lot today and, to take it back to Megalopolis, what would you say is the defining image of the film?

That’s a good question. I want to go in two different directions with this but truthfully, it’s probably the end where we finally see the future city. It’s in Central Park while the rest of the city is mostly unchanged, if I remember correctly. I think that’s it. Megalopolis is a movie of “limitless creativity,” at least until it reveals that the instinct that produced that limitless creativity is, in fact, limited. That kind of said it all to me. People were making jokes about it but it bowled me over when I saw it. I heard a lot of snide remarks like, “It’s just in Central Park,” but there’s a humor to that. I'm not disagreeing that it’s funny but when I saw that in the theater, I was like, “Oh my god, Caesar is a charlatan.” So I would say that’s the keystone to understanding the picture.

Is there a defining image like that for cinema as a whole?

Oh, boy. [Pauses to think]

I feel like something must have popped into your head.

Yeah, it did. I don’t even want to say it because it’s so trite but it’s probably Anna Karina watching The Passion of Joan of Arc in Vivre Sa Vie. That’s as close to a defining image as you’re going to get. I like Godard filming his TV set with his camera in JLG/JLG – Self-Portrait in December. That kind of that kind of speaks to that as well. But the great thing is there isn’t one. You don’t have to choose. It’s limitless. I don’t really have an imaginative answer for that one.

I think we can work with that. This was so great, thank you for taking the time to talk to me.

Sure thing, this was fun.

You can subscribe to Alex’s Substack, More Like Shit Stack, here. You can also follow him on Twitter and on Letterboxd.