It feels trite to use this, admittedly modest, platform to offer the umpteenth reflection on where we are as a culture — instead of discussing what cinema will look like now that the superhero genre is floundering and Mattel-core seems poised to take its place, we should perhaps be asking ourselves what we want cinema to look like moving forward — so I won’t do that here. This is not to say that investigating these things is a waste of time but rather that I’m happy to leave these inquiries to people who feel compelled to engage with the likes of Barbie, The Super Mario Bros. Movie, or, God forbid, The Eras Tour, three commercially successful and, in the case of Barbie and Eras, highly acclaimed works that, to this critic at least, suggest about as much enjoyment and nourishment as unseasoned rat poison.

Any year-end list worth its salt shouldn’t be a bid for relevance or used as an easy way to weigh in on the dreaded, all-consuming Discourse, nor should it be a measure of some nebulous ideal of perfection. In an age where art strives to be for everyone, the films on this list are defiantly half-baked in spots, indulgent in others, ideologically messy, sometimes sterile, and not seldomly melodramatic. In lieu of drab, four-quadrant “perfection” they offer unique artistic visions that run the gamut from directorial-debut eagerness to late-style interiority and for that reason alone describing them as “courageous” feels nothing like the pretentious overstatement it so easily could be. The world, and cinema in particular, could use a lot more courage — hopefully some of the films on this list can offer us a glimpse into a world where it isn’t in tragically short supply.

(Note: for consistency’s sake, I’m going by U.S. theatrical or streaming release date.)

28. Animalia

While the film’s post-desert revelation musings on the universe and human interconnectedness aren’t quite the payoff one would hope for after the intriguing and exceedingly well-crafted hour that preceded it, this does pave the way for a beautifully surreal final image: a lush landscape full of rich green, dissolving slowly into a starry night sky. It’s an image that, combined with the ponderous voiceover, evokes something supposedly remarked by Kafka to a seventeen-year-old Gustav Janouch: “Life is infinitely great and profound as the immensity of the stars above us. One can only look at it through the narrow keyhole of one’s personal experience. But through it, one perceives more than one can see.” Alaoui doesn’t quite knock it out of the park with her feature film debut, but her willingness to dwell on the obscure and meditative makes the prospect of a follow-up very exciting.

Read my full review of Sofia Alaoui’s Animalia here.

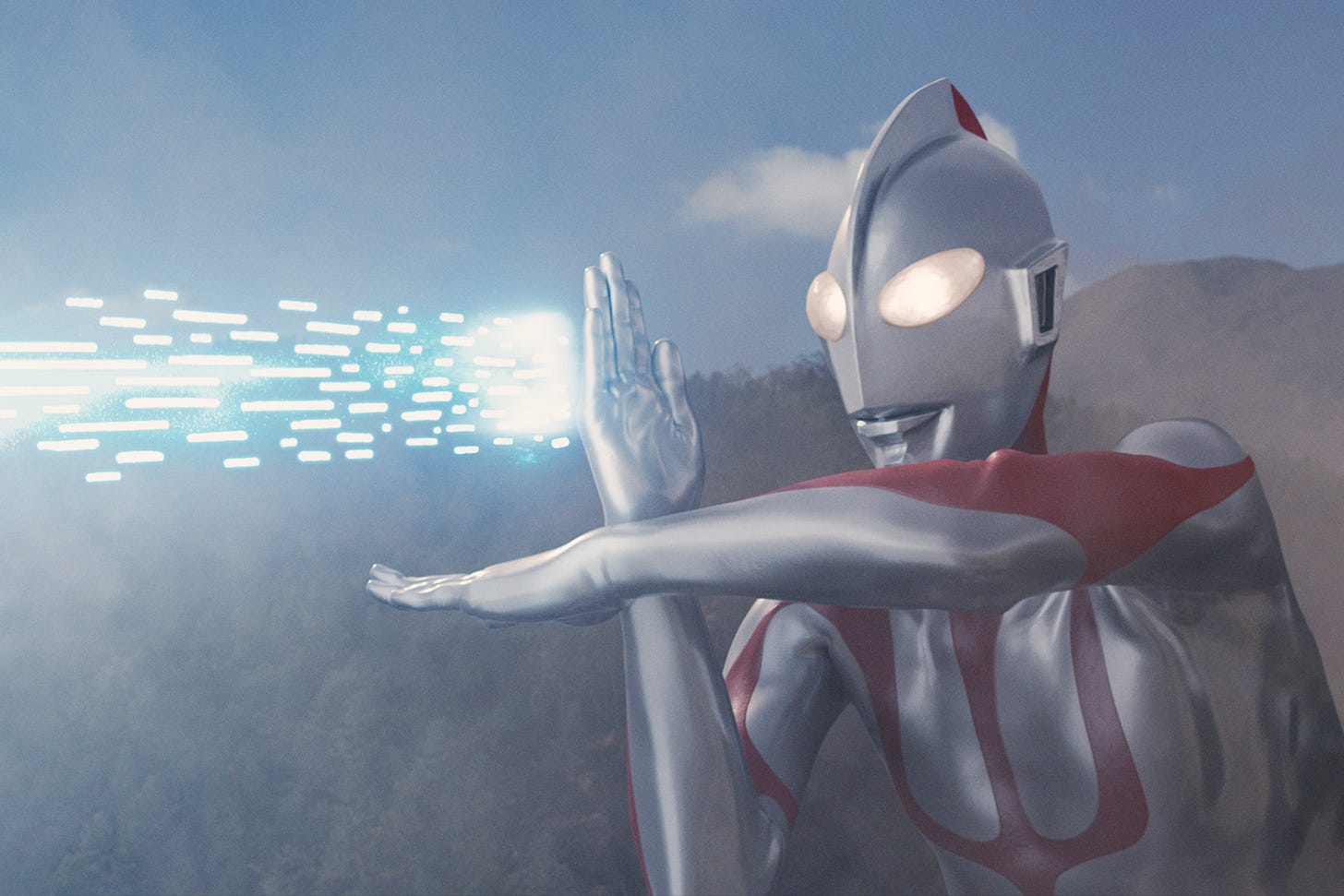

27. Shin Ultraman

Overall, the film operates with a rather chaotic, villain-of-the-week momentum that occasionally threatens to spin things out of control. The tone constantly ricochets between serious and silly, philosophical and melodramatic, and for some, the results will likely skew closer to numbing than engaging. There’s also sure to be a contingent of Anno devotees who bemoan the absence of Evangelion’s esoteric subject matter and the arthouse weirdness of his first two live-action features, as his script once again sets its focus on the structural rather than the existential. But the filmmaking duo feels at home with this material — perhaps strangely so in Anno’s case — and their brand of pop nostalgia feels alive, intelligent, and passionate in a way that Hollywood’s current onslaught of cynical IP rehashes and cinematic universes simply haven’t.

Read my full review of Shinji Higuchi’s Shin Ultraman here.

26. Oppenheimer

Not everyone was convinced Christopher Nolan could pull it off but the director, most famous for his trilogy of Batman films as well as the dreamworld-set sci-fi thriller Inception, not only propelled his stern, narratively intricate J. Robert Oppenheimer biopic to almost $1 billion at the box office — the third-highest-grossing film of the year, flanked on both sides by IP fare and sequels (with the exception of Zhang Yimou’s Full River Red) — but also proved the naysayers wrong by crafting his most heart-pounding and politically intelligent film yet. The latter might not mean much in light of the empty-headed national-security centrism some of his previous work was bogged down by but watching an artist grow beyond themselves in such spectacular fashion is a true joy.

25. The Five Devils

It’s all here: generational trauma, repressed queer desire, (bi)racial strife, magical realism — the works as far as contemporary arthouse features go. But Léa Mysius’ film is more than a collection of trendy gimmicks designed to rope in well-meaning liberals looking for something to affirm their sensibilities (that isn’t made by a Hollywood slop factory). Mysius’ second feature after 2017’s aquatic Ava brings real dramatic heft to its existential musings and opaque character entanglements as it imbues its coming-of-age tale with a supernatural twist that is wonderfully odd and oddly affecting in its specificity. It also happens to contain some of the most powerful images out of any film released this year.

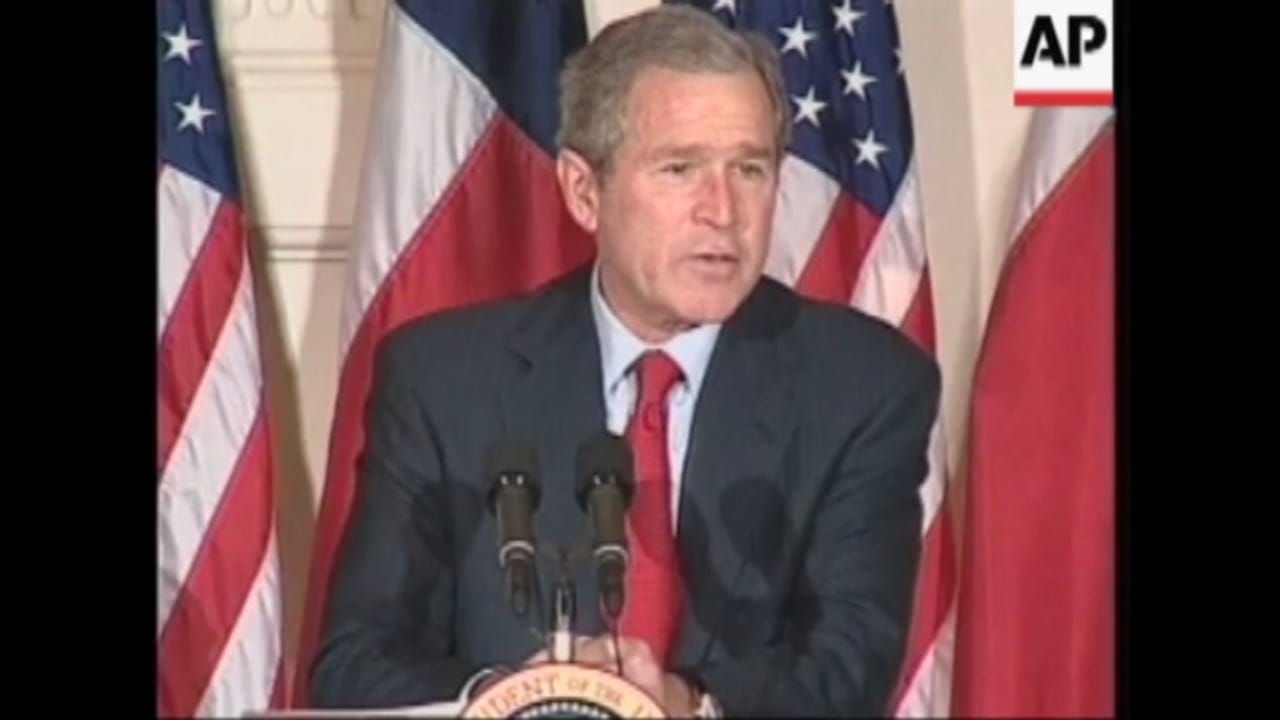

24. Miss Me Yet

The Trump presidency brought with it so much chaos and unprecedentedly naked reactionism that, thanks to a shockingly short collective memory, people yearned for times of order and civility — completely forgetting how ugly the face of “order” truly is. Christopher Jason Bell hasn’t forgotten, however, and his Bush administration documentary not only collects the crimes and other assorted misdeeds of one of the worst mass murderers of the 20th century but also captures the paranoid ambience — which unsettlingly coexisted with braindead escapism — of the post-9/11 world via ads, TV bumpers, government press conferences, and news reports. “History repeats itself, first as tragedy, second as farce.”

23. The Sweet East

Sean Price Williams’ feature-length debut The Sweet East, a kind of picaresque hangout dramedy preoccupied with our sociopolitical moment, truly succeeds as a work of uninhibited cinematic amalgamation. The scuzzy ‘70s aesthetic is interrupted by nods to the silent film era — at one point, two characters come to an overlook in the forest and the film makes use of a painted backdrop, a moment of sudden, bizarre beauty — and D.W. Griffith in particular is referenced through the use of title cards, pastoral locations, and even lines of dialogue cribbed from an unproduced Griffith play.

The Sweet East’s shooting gallery of post-Trump caricatures, meanwhile, is rendered with a cool-kid cynicism — courtesy of film critic and screenwriter Nick Pinkerton — that trends towards the juvenile in its equal-opportunity skewering of erudite closet fascists, sex-pest anarchists, and big-city artist types. But it’s also undeniably funny, well-acted — Talia Ryder is magnetic, Simon Rex expertly pulls off a different kind of scumbag from the one he played in Red Rocket, and Jeremy O. Harris and Ayo Edebiri’s duo provides some of the film’s funniest moments (“Sometimes the best actress is just a woman who says ‘yes.’”) — and refreshingly uninterested in lecturing its audience.

22. The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial

Leave it to William Friedkin to go out with a decidedly unfashionable courtroom drama. The late New Hollywood enfant terrible, best known for his gritty 1971 crime thriller The French Connection and the 1973 horror classic The Exorcist, was no stranger to single-location shoots — the claustrophobic Bug (2006) took place largely in a motel room — and The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial looks and feels like the work of a master exactly because of how elegantly he operates within this constraint.

Amidst the ultra-clean digital textures, neat uniforms, and sparse interior design, the white-knuckle action set pieces of his ‘70s masterpieces are obviously completely absent but at times the script reads like something right out of the Nixon years. Not only are there outdated slurs — it’s probably been a few decades since anyone used the term “Polack” in real life — but the film ends with a final speech that is sure to turn quite a few progressive-minded viewers off. Friedkin always had a penchant for provocation so perhaps ending his legendary career on one feels more than appropriate — and either way, seeing the late Lance Reddick shine one last time is its own reward.

21. Afire

Of being a pompous stick-in-the-mud at the end of the world. Christian Petzold’s portrait of the artist as a misanthropic asshole moves along with a tragic sense of inevitability, pulling twentysomething ennui from its usual navel-gazing sphere and confronting it with something more tangible. Much like the climate collapse barrelling at us in real life, the fiery apocalypse that hangs over the characters’ already awkward vacay in the woods (Thomas Schubert’s try-hard coffee-and-cigarettes novelist Leon is, of course, the main source of the tension) remains an abstract, far-away phenomenon for the characters, something to be gawked at and worried about from the safety of their idyllic holiday home — that is, until it does eventually, inevitably, catch up with them.

20. In My Mother’s Skin

Kenneth Dagatan’s creepy body horror fairytale is a beguiling genre amalgam which combines folkloric terror, historical tragedy, and shades of J-horror. When the fairy’s supposed miracle cure inevitably sets in motion a bizarre transformation, Ligaya’s body contorts uncomfortably, and her voice crackles with blood-curdling menace, recalling Kayako’s eerie death rattle in Ju-On: The Grudge. Obvious parallels to Guillermo del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth aside, In My Mother’s Skin grafts its more fantastical elements onto something altogether more nasty, even as it looks at the world through the innocent, naïve eyes of 14-year-old Tala. Mangled corpses and severed heads abound, punctuating — maybe “interrupting” is the more apt descriptor — the film’s deliberate pacing. There are kaleidoscopic shots of rich flora blossoming around the characters throughout the film’s 97 minutes, and their oneiric blurriness — reminiscent of Carlos Reygadas’ 2012 magical realist Post Tenebras Lux, as well as the works of Apichatpong Weerasethakul — counters the cold, sharp, gray interiors of the barren family manor.

Read my full review of Kenneth Dagatan’s In My Mother’s Skin here.

19. Copenhagen Cowboy

Given that the line between film and television has been irrevocably blurred in the age of streaming, the inclusion of Nicolas Winding Refn’s latest dronecore spectacular feels appropriate. Refn already made his case for streaming as a viable avenue for auteurist expression with 2019’s Too Old to Die Young and Copenhagen Cowboy is best understood as an elaboration on the Danish director’s artistic pedigree: extreme violence, degenerate characters, and neon-drenched excess. As his style continues to trend towards the solipsistic, the miniseries format is proving itself to be a perfect match for Refn’s current thematic and aesthetic obsessions.

18. Trenque Lauquen

Laura Palmer in Twin Peaks; Laura Hunt in Laura (1944); Laura de Noves, the subject of countless romantic Petrarch sonnets: throughout art history, the name “Laura” has evoked elusive, unattainable women — sometimes made unattainable by an untimely death — and there is a trinity of Lauras at work with Trenque Lauquen, an elliptical mystery drama directed by Laura Citarella, co-written by Citarella and Laura Peredes who also stars as, you guessed it, Laura, an academic who has gone missing. From a simple premise, Citarella concocts a sprawling narrative that unfolds across twelve chapters and two parts that both exceed two hours.

The generous runtime allows her to explore romance, history, and the very art of storytelling and the film even hints at cryptozoology with a lake-related mystery that pops up in the second half. But the questions that litter the story are ultimately less important than the grip they have on the characters and Citarella doesn’t treat the elusiveness of truth as cause for despair but as something to marvel at and lose yourself in.

17. Killers of the Flower Moon

Few, if any, filmmakers have chronicled the lives of awful men more excitingly than Martin Scorsese has but after the degenerate exuberance of 2013’s The Wolf of Wall Street, his work took on a more somber tone as he entered the autumn of his filmmaking career. Killers of the Flower Moon’s opening is the only flash of the ecstatic Scorsese style of old as the rest of the film settles into the deliberate rhythm of real-life tragedy, recounting the story of the Osage murders in 1920s Oklahoma.

But Killers doesn’t just grapple with the racist evil of a glossed-over chapter of American history but also points towards its echoes in the present — it’s easy to see shades of Robert De Niro’s William King Hale in the powerful men currently making people’s lives a living hell — as well its own inadequacy in telling this story. This isn’t ancient history — the Jazz Age was already underway by the time these murders were carried out — and out of all the things Scorsese leaves us with, the realization of just how little has changed, how little closure there actually was, might be the most distressing.

16. Walk Up

For a filmmaker whose style is so often treated as easily identifiable, it can be surprisingly hard to sum up Hong Sang-soo’s whole deal as each of his films offer a different spin on the talky, intimate, and often soju-fueled dramas that have made him a name amongst cinephiles. But while the formal and narrative constraints he imposes on himself have sometimes prompted a little good-natured ribbing even from his admirers, it has caused some to miss the eeriness at the center of Walk Up, a temporally fluctuating film whose diverging realities spin out into something surprisingly dark and strange. With Hong, time is often a slippery thing but combined with his hyper-focus on the architecture his characters navigate, that slipperiness has rarely been used to such haunting ends.

15. Mami Wata

For Western audiences, questions of spirituality are unavoidably perceived through the lens of Christianity or Abrahamic religion more generally so seeing Nigerian director C.J. “Fiery” Obasi bring a different perspective to the subject is an invigorating experience on that basis alone. Luckily, familiarity with the titular Mami Wata, a water spirit venerated in large parts of Africa, isn’t a prerequisite for engaging with his gorgeous black-and-white supernatural thriller, as Obasi’s concerns extend beyond the spiritual and into the realm of politics, Africa’s conflictual, bloody history in particular — bold thematic ambitions which are rounded out beautifully by Lílis Soares’ striking, dreamlike cinematography.

14. All Eyes Off Me

Ben Aroya refrains from ever moralizing about her characters’ habits and inclinations, however, choosing to observe their behavior with a refreshing lack of judgment. When she brings up young people’s oft-discussed propensity for constantly pulling out their phones, her characters indulge the habit with a level of self-awareness that feels indicative of a deeper empathy she has for those at the heart of her film. Further, the writer-director also shows them interacting earnestly with the technology that’s become so ubiquitous in our daily lives. Far from the blank-faced passivity that members of her generation have been caricatured with, Avishag is genuinely moved to tears by a vocal performance she watches on YouTube during a quiet moment — a startlingly genuine reaction, perhaps only made possible by her solitude.

Read my full review of Hadas Ben Aroya’s All Eyes Off Me here.

13. Sick of Myself

It’s undeniable that there is an air of smugness around how Borgli critiques contemporary culture and it could similarly be argued that he’s going for very low-hanging fruit as even societal dislike of shameless egomaniacs has been folded back into the very spheres they thrive in — these days, those skewering influencers end up with the same brand deals as their non-ironic counterparts. But seeing just how low his characters are willing to go in pursuit of notoriety is at once hilarious and heartbreaking. When Signe’s “tell-all” interview, conducted by her journalist friend Marte (Fanny Vaager), gets bumped down in favor of a story about a deadly shooting, Signe becomes irate — “What fucking nerd shoots his whole family?” — angrily calling Marte up to see if there’s a way to make herself the top story again.

Read my full review of Kristoffer Borgli’s Sick of Myself here.

12. The Killer

Fincher harnesses his Gen-X style of subversive irony — a concept that seems almost quaint in an age where power has embraced it so enthusiastically — not to dissect Fassbender’s character but rather the ludicrousness of his self-image and supposed code while operating as just another cog in the machine. He rents cars, flies economy, checks his Fitbit, sleeps in spartan hotel rooms, and eats at McDonald’s (while being mindful of his carbohydrate intake). This is what the story of a man driven by revenge looks like in the 21st century: an endless procession of commercial spaces, waiting in line, staving off boredom. Whether or not he’s actually good at his job is entirely inconsequential because, for all his pontificating, he’s just as much of a working stiff as everyone else trying to survive the gig economy — “the same decaying organic matter as everything else.”

Read my full review of David Fincher’s The Killer here.

11. The Plains

Shown in long, unbroken takes; taking place almost exclusively in a car; and running for three hours, David Easteal’s docudrama The Plains (his feature film debut) has all the markings of a tough sell. But the film is neither an indulgent arthouse experiment — not that there’d be anything wrong with that — nor a sentimentalist “celebration” of the mundane. Instead, Easteal reconstructs reality: the two men did, in fact, frequently commute together when they both worked at a community legal center in Melbourne. This proximity, born out of a combination of convenience and kindness, eventually developed into a friendship as Easteal and Rakowski got to know more about each other and their lives with every shared trip.

Read my full review of David Easteal’s The Plains here.

10. Ferrari

Michael Mann’s Enzo Ferrari biopic is something of an anomaly: while its themes bear the hallmarks of late-period self-reflection — unsurprisingly, the story of a male visionary blindly devoted to a stubborn ideal of greatness at great personal cost to himself and, crucially, others resonated with the director — its form harkens back to Mann’s earlier work, perhaps owing to the fact that he first envisioned the film three decades ago. Starting with 2004’s Collateral, the filmmaker has been consistently preoccupied with the digital world — a fixation which reached its zenith with 2015’s Blackhat, Ferrari’s predecessor — but here, Mann lets jarring moments of digital intrusion collide with the otherwise more traditional style.

There’s a palpable sense of danger that permeates Ferrari’s every frame, particularly heightened during the thrillingly shot racing scenes. Engines roar with menace and death perpetually looms on the margins, waiting for an unfortunate soul to succumb either to their own recklessness or an ill-timed mechanical failure. Collateral damage in a man’s ruthless quest for glory — and yet one can’t help but be captivated watching cars speed through the lonely night, the road illuminated only by their headlights. For just a moment, we understand the obsession. What could be more Michael Mann than that?

9. Human Flowers of Flesh

As if the comparisons to Claire Denis’ Beau Travail weren’t inevitable enough, Denis Lavant pops up during Human Flowers of Flesh’s final minutes to reprise his iconic role as Adjudant-Chef Galoup. But Helena Wittmann’s film, whose death metal-esque title happens to recall the second entry to the controversial Guinea Pig film series, 1985’s Flower of Flesh and Blood, is more than an empty homage. The German filmmaker’s second feature might not probe into the repressed sexual dynamics of the French Foreign Legion as deftly as Denis’ classic does, it does succeed at conjuring a hypnotic mood that’s all its own.

8. Shin Kamen Rider

Like previous Shin entries, Shin Kamen Rider doesn’t bother with easing the audience into its bonkers whirlpool of critter-themed superhumans, mad scientists, and dead bodies that disintegrate like defeated enemies in fifth-generation console games. Anno hits the ground running and crams every scene with either exposition, comic-book violence, or pathos-laden monologues. Given the source material, the film, like Shin Ultraman before it, is episodic in structure, with the two leads essentially being ushered from set piece to set piece as they take on SHOCKER’s gallery of overpowered foes, each with their own deranged vision of bringing about world peace. (Not incidentally, SHOCKER’s name and objectives deliberately echo SEELE’s Human Instrumentality Project in Evangelion.)

Read my full review of Hideaki Anno’s Shin Kamen Rider here.

7. May December

Todd Haynes melds Sirkian melodrama with Ingmar Bergman’s Persona and infuses it all with black humor and music stings ripped straight out of a soap opera. It’s a complicated, thorny amalgam, one that is all the better for pointedly refusing the moral shallowness demanded of art these days. Intriguingly, May December doesn’t shy away from its own complicity in perpetuating the gross spectacle — the final scene in particular suggests something profoundly absurd and perhaps even sinister about Elizabeth’s (and indeed the film’s own) endeavor — but as last year’s Blonde controversy so beautifully illustrated, art will ultimately always be uncomfortably tangled up in the real-world horror that inspires it.

6. Yanagawa

A shared romantic obsession with a childhood friend leads two brothers from Beijing to reconnect for a trip to Yanagawa, a sleepy Japanese town called “The Venice of Japan” owing to its canal system, complete with gondolas manned by singing gondoliers. But instead of bustling streets crowded with tourists, the brothers find a sleepy working-class town that offers about as much excitement as a dying mall. They do, however, come across their friend who left their lives without a trace all those years ago and their reunion opens up old wounds as well as new opportunities to face the past.

Director Zhang Lu isn’t concerned with arbitrary notions of narrative momentum but instead offers plenty of quiet character moments, careful blocking, sustained shots, and a tranquil atmosphere that is so peaceful, it might just cause some viewers to drift off into a restful sleep. It’s true that this serenity belies a heavy-heartedness that colors the trio’s conversations and drunken late-night wanderings but it is staged with such delicacy, one can’t help but feel at home in its embrace.

5. Limbo

Trash, rain, sweat, and blood abound in Soi Cheang’s hellish action-noir ripper. Set in a dystopian megalopolis, Cheang’s über-gritty detective story portrays a decaying society, overflowing with poverty, violence, and garbage. Its atmosphere is relentless, the film’s mesmerizing black-and-white cinematography and waste-littered production design recalling Tetsuo: The Iron Man’s wriggly cyber-junkyard aesthetic. Limbo occasionally veers into horror territory owing to its intensely bleak scenes of murder and mutilation but it also boasts a surprisingly engaging human drama underneath its nasty exterior, which grounds some of its more unpleasant, though disturbingly effective, genre excesses.

4. In Water

While Hong’s decision to shoot almost all of In Water (frequently stylized in lower case) out of focus is hardly the most noteworthy thing about it, it does add an interesting wrinkle to his ongoing exploration of creativity and his anxieties about his own career and advancing age — notably, his avatar this time around isn’t an established, middle-aged director but a youthful actor with directorial ambitions — as worsening issues with his eyesight have coincided with him taking on more and more production duties, including cinematography and editing.

What could’ve easily been a distracting gimmick actually takes on a rather melancholy quality — it also largely obscures the character’s facial expressions, a big part of what makes Hong’s low-stakes dramas so alluring — as In Water further blurs the line between flimsy fiction and the auteur’s real life. But even as its presence is felt continuously across the film’s brisk 61-minute runtime, Hong’s ongoing dedication to finding inspiration and beauty in the mundane lingers long after the moving coda which gives the film its title.

3. Pacifiction

Catalan cineaste Albert Serra’s post-colonial slow-burn thriller plays like a strange, slow, unstoppable descent into a hell of decadence and paranoia. Following the shady dealings of a French official in Tahiti, Pacifiction sheds some of Serra’s slow-cinema sensibilities in favor of a structure that is more approachable, immediate — and sinister. Its lush panorama of beaches and gorgeous vegetation contrasts ominously with the nuclear anxiety that saturates the sparse, barely legible plot. This fascinating juxtaposition may not bring anything new to the table in terms of confronting France’s legacy of colonialism but rarely has its long shadow been captured with this much unceasing menace, culminating in an infernal final shot.

2. Master Gardener

The first two entries into Paul Schrader’s “Man in a Room” trilogy — 2017’s First Reformed and 2021’s The Card Counter — brought the filmmaker back into critics’ good graces after spending the previous twenty years in an artistic limbo, pushing out a steady stream of widely derided (though occasionally underrated) works that led most believe his glory days were behind him. Now, a few years into his late-career renaissance, the legendary writer-director strikes a chord that is markedly different: after meeting alienation, isolation, environmental destruction, and institutionalized violence with anger — his films often culminate in bursts of vicious, cathartic violence of their own — Master Gardener sees him contemplate hope and rebirth in a way he hasn’t before. As he said at the 79th Venice Film Festival where the film premiered and he won the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement: “I used to be an artist who never wanted to leave this world without saying ‘fuck you,’ and now I’m an artist who never wants to leave this world without saying ‘I love you.’”

1. Knock at the Cabin

It’s admirable that M. Night Shyamalan has stuck to his guns the way he has considering his intelligence is routinely underrated or called into question outright by critics and audiences more eager to get their licks in than engage with his work in good faith. But there’s no two ways about it: Knock at the Cabin is Shyamalan’s greatest, most moving work to date, a beautiful parable reflecting on faith, love, and sacrifice. It’s also a film whose theological convictions are bound to be misunderstood — if they are seriously considered at all — as most mainstream cinema retreats further into self-awareness and can only muster limp sentimental scientism (repackaged as “positive nihilism”) in response to our societal and spiritual crisis.

The high-concept premise of four strangers holding two fathers and their adopted daughter hostage, claiming one member of their family will have to willingly sacrifice themselves in order to save the rest of humanity, provides an ideal jumping-off point for the director to indulge in yet another intensely claustrophobic genre exercise. Shyamalan, having fully let his style off the leash with 2021’s Old, softens some of his more eccentric impulses to suit the emotional tenor of the script but nonetheless dazzles with unorthodox compositions, bold camera movements, and startling close-ups of tormented faces.

The fact that the family being held hostage is headed by “a single-sex couple,” as Dave Bautista’s Leonard so carefully puts it, adds another layer to the tense dynamic between the family and the intruding quartet. One of the fathers, Andrew (Ben Aldridge), is convinced they are being targeted by bigots, a conclusion shaped by a lifetime of homophobia and a particularly traumatizing instance of violence. Eric (Jonathan Groff), by contrast, spends the first hour in a concussion-induced fog from which he only slowly emerges, making for a more sedate presence next to the desperate and angry Andrew.

Seeds of doubt are sprinkled throughout but these pose more of a challenge for the captives than they do for the audience. Shyamalan has never been one for subtlety so the question of how true the intruders’ claims are soon gives way to the question of whether or not the family will be able to make the sacrifice that’s been asked of them. But is humankind even worth saving? Andrew isn’t so sure: “How about I show you photos of kids who have been tortured and killed, lying in piles?” he asks Leonard. “You want to make a case for humanity to go on, you’re gonna lose.”

And yet even when acknowledging humanity’s darkness, Knock at the Cabin remains uninhibited in its belief in the future. Faced with the end of the world, Shyamalan doesn’t stoop to misanthropy, nor does he offer platitudes or cheap cynicism. His vision of faith is unquestionably a frightening one — why would a loving God force anyone to make a choice as impossibly cruel as that? — one that melds Lovecraftian horror with Jobian anguish. Job looked beyond himself while in the throes of immense suffering — “For I know that my redeemer liveth, and that he shall stand at the latter day upon the earth.” (Job 19:25) — and with his latest, Shyamalan invites us to do the same. The skies will eventually clear up again — all we need is a little faith.

Thank you for the recs and beautiful write up ❤️

Hell yeah. This is great. So many flicks I still need to check out!